Back from 6 weeks of travelling in Amdo, how to condense all that happened into a blog-sized epic without it getting long and tedious? Perhaps sectioning the trip off into the different areas will make it easier for all of you to read without being bored silly…

Part 1 Chengdu – Xining – Thrika

Finally the last days passed before I was to leave. The primary classes I teach on Saturdays are not my favourite part of the week at the best of times, but the Saturday I was to leave they seemed to last forever. However, all things do come to an end, slow in coming as it may seem, I gulped down a huge lunch they had prepared in honour of my leaving, and dashed off to collect my backpack and head to the station. Spent that night in Chengdu, prudently investing in an extra set of thermal long-johns before getting on the train the next day. The train was a pleasant surprise. After years spent travelling on Indian trains, and growing accustomed to arriving at one’s destination absolutely encrusted in sweat, soot and grime, it was nice to have spotlessly white sheets, duvet and pillow, heating, and a window one could actually see out of. The only thing I missed about the trains in India was the food and drink service. On trains here, hot water is available, but everyone brings their own food. I admit to missing the chai-wallahs going up and down the cars shouting “chai, chai…chai garam!”. Sat glued to the window for the daylight hours of the 26 hour trip, watching the landscape change from the lush greenery and rolling hills of Sichuan for the craggier cold landscape of the north through Gansu and into Qinghai. Woke up the next morning, pulled aside the curtains, and saw snow! Straight into the reality of winter in Amdo. And I’d been whingeing about the cold in Sichuan. ( As those of you who know me well, I whinge about cold pretty much anywhere…!) It was beautiful though, as we continued north, and the landscape grew more and more open and unpopulated. The part of Sichuan where I live is beautiful as well, but is a bit like England in that there are no real spaces that are open and untended,

Passing through Lanzhou, it started to feel as though I’d come home, as we entered the more obviously Tibetan areas, houses and villages with prayer flags and darchog , wisps of juniper smoke curling on the breeze. Finally arrived in Xining, was swept off the platform and into the station on the crowds of students and passengers heading home for the holidays, and was met by R---, bundled into a taxi and headed off to her brother’s home. It felt indescribably odd to be sitting at last in a city of which I had heard so much from so many friends. Lovely to see her again as well. She’d come to study in Gomang during her summer holidays, and has been back here for a couple years. She’s just passed her tour guide exam, so will be going to work in Lhasa for the summer. Another friend in town is P----, who I used to know as Lhungrik years ago, when he was my best student in northern India. He too, is a tour guide, and has his own travel agency. R---- and I went out for dinner with him and his family, the Qinghai version of huoguo! Not nearly as spicy as the Sichuan style hotpot. Xining is really a “cowboy” sort of a town, very much as one would imagine a slightly more modern version of a Wild West frontier town. Lots of neon lights at night, but still very much a border town, especially compared with the sprawling mass of Chengdu. An interesting mix of people though, Chinese of course, Tibetans in traditional chubas and a large Muslim community. There are several large mosques, along with the usual temples, and the streets are full of Muslim men with their spotlessly white caps, and women with their headscarves. Didn’t spend much time in Xining on the way up though, heading out the next day with M----- to visit his home in O-Jo monastery, in Thrika county. I have been unable to find this on a map, and don’t even know exactly what direction from Xining it is! The air seemed to get colder as we drove, heading higher into the mountains, and when the bus stopped halfway, we got out to take some photos of a large “ice sculpture” made by spray from a hose used to wash down the buses on the way back to the city. Driving through the Tibetan villages on the way to the monastery, my attention was divided between catching up on news and monk gossip from M, and looking out the window, watching a whole way of life I’d been hearing about for years pass by. Village woman in thick chubas lined with sheepskin bent nearly double under woven baskets trudged along the roadside, looking up as we passed, only bright eyes visible in faces wrapped with scarves against the biting cold wind. Herds of sheep and goats heading home on the road sauntered along, oblivious to the bus driver honking his horn furiously at them, their diminutive shepherdess staring up at the windows, letting the sheep slowly move to the side of the road at their own speed, the huge mastiff with her looking fiercely at the bus tires as if trying to find a vulnerable spot to attack.

Finally we pulled off onto a bumpy dirt track, bouncing along for a kilometer or so until the whitewashed walls of the monastery came into sight. As we entered the monastery gates, several monks came running up with kadags (white blessing scarves) and led us away to the kitchen for dinner after depositing my bag in M’s room. As it was already growing dark, there was little point in looking around the monastery that evening, so we sat and chatted, catching up on the news of the past couple years. M has been working hard since returning here, starting up a holiday-school for students to do extra study during their school holidays. There are about 90 students, ranging in age from 12 to 20-ish. To attend the monastery school, they must study Tibetan, then can also choose to study English (taught by M! My old student is now a teacher!) and/or Chinese, taught by a girl attending university. I was impressed at how well he had set it all up. He has worked really hard, and put in a lot of time. While the kids are back at school, he himself goes to study English grammar himself in Xining. The next day, I taught the English class, and we played some games with them, then wandered off to do some exploring. M took me to visit the Jowo-khang temple, one of the holiest pilgrimage sites in Amdo, where most pilgrims visit before setting off on their pilgrimages to Lhasa.

After that we returned to the monastery, and had a look around the monastery grounds, in the prayer hall, and at the Cham masks hanging in a dark room upstairs in the prayer hall, which greatly amused two young boys who tagged along after us. The elder was quite happy to model the masks for us, but the younger was a wee bit unsure until the cameras came out, and then his fear miraculously dissolved. Clambered up a rickety ladder onto the roof, to have a look round, and watched a few monks playing an adaptation of volleyball with a net M had rigged up, made of kadags tied together! (I giggled quietly to myself wondering about what blessings the ball was receiving as it soared over all the white silk auspicious symbols…) But my time in Thrika was all too short, as I was under orders from C and the others at Tharshul to get myself there ASAP. So the next morning, I climbed onto a local bus full of nomads, waved goodbye to M, and set off for Tharshul.

Part 2 Tharshul, C’s family and New year

OK, stretch out the kinks, take another swallow of coffee, and settle yourself in for the next bit! The bus ride from Thrika was unbelievably cold. I was sitting in the seat right beside the door, and as we kept stopping to allow people on and off, my feet slowly froze into blocks of ice, until an hour into the 4 hour trip, they were completely numb, with no feeling no matter how hard I stamped them. However, having no one to whinge to about the cold, I decided to be stalwart about the whole thing ( I know, it’s not like I had any option, right?!) and was instead entertained by the conversation the nomads were having about me, which translates roughly into something like this:

“ Look, there’s a Mey-go girl (American – the only foreign country many of them have ever heard of), have you ever seen one before?” “ No, never. But her hair isn’t very yellow.” “ No, but her eyes are blue!” Really? Let me see! ( At this point she leaned over to look at my face more closely) “ Hey look, she is smiling, do you think she understands Tibetan?” “ No, I’m sure she doesn’t. Wonder where she’s going?”

So the long ride passed quickly, as I happily listened to them discuss me for hours, since every time a new passenger got on, the whole thing discussion would be repeated, the earlier passengers happily telling the new arrival “all about me”. I was sorely tempted to say something in Tibetan just to see what they’d do, but figured it was more fun listening, hard as it was to keep from laughing. And the scenery was more than enough of a distraction. It’s hard to believe how many different types of mountain we passed in the space of a few hours, from gently rounded hills and steep, roughly striated cliffs, to craggy mountains with sand dunes blown into their crevices. And the higher we got, the colder and snowier it became, until we finally drove triumphantly over a pass, with all the passengers opening the windows, and shouting “Lha gya-lo” (may the gods triumph). As we approached the town of Guinan Dzong, where I was to meet C before going to Tharshul, the high snow-covered grasslands dotted with herds of yak and sheep gave way to a cluster of houses. Pulling into the station, I scratched a hole in the frost on the window and saw C, K, and several more old friends waiting with kadags by the station gate! Just like coming home. I staggered off the bus trying to stamp feeling back into my feet, and was greeted by the whole horde of them, accepting kadags, laughing and talking at once as they hauled my snow covered pack off the roof of the bus, and then hauled it and me into a nearby restaurant, sitting me in front of an electric heater to defrost, before ordering an absolutely huge lunch. It had been years since I’d seen most of them, so there was much to catch up on as we ate, then piled into a taxi-van and drove yet higher still into the mountains to the monastery, over an incredibly bumpy road, bouncing back and forth over, through and in the bathtub sized potholes. After 20 minutes or so, the monastery gates came into view, and as we drive closer, we saw another group of monks waiting: N, S, and several others who’d come to meet me. Unloaded my pack first at C’s room, hung out for a bit and chatted with everyone.

After a couple hours, was moved up to D’s room, where I was to stay for the weeks of my visit. He had a roommate who was away for Losar, so had a room to myself, complete with electric blanket! Oh joy! Oh bliss! Not terribly healthy, perhaps, but soooo toasty warm! After spending three weeks living with D, his two students, JT and G, and his dog, Pasang, we became quite the little family. Spent a lot of time joking and laughing. Unfortunately, the next day I was flattened by a wicked cold which I’d gotten from freezing on the bus ride over, but was determined not to let it slow me down, so though I couldn’t teach the English classes C had asked me to that first day, I did hang out with him and listened to his classes, sniffling away, and trying to ignore a wicked headache. C was learning English right from the start, as well as being in the art club, and it was easy to pick up our friendship where it had left off. The next day my cold was worse, so since the monastery doctor was also sick, D gave me an IV with glucose and cold medicine, and I didn’t teach that afternoon either, went early to bed that night, and was fine the next

day.

For the next week, I taught the English classes for the school kids on holiday, as well as an ABC class for a group of monks. Always did enjoy the beginner classes, and it was a group of really bright and funny young monks who were not at all afraid to speak.

Over the next few days, went for walks round the monastery and surrounding area. Tharshul is nestled in a semi circle of snow covered hills, looking out on a wide valley of snow encrusted frozen grassland dotted with the homes of nomads, and the smaller specks of black on the hillsides which are the herds of yaks. The monks assure me the area is stunningly beautiful in the spring and summer when all the wildflowers are out, and I can well imagine. On clear, snowless days, the sky is the deepest of ultramarine blues, and the snow is so white it hurts the eyes. After the smog and damp fog of Chengdu, the clean air is wonderful, though I was quite breathless the first few days because of the altitude.

On days when the monks went to prayer, I wandered about myself, going for long walks up into the hills, to the retreat centre and the prayer flag poles, or down into the valley to the mani-khang temple near the nomads’ homes. Walking down the icy rutted track past the herds of yak, the wind blowing my hair in my face, listening to the snow birds chirping, and watching the small lemming-like creatures waiting til the last moment of my approach before scurrying into their holes, I was so happy it almost hurt. High up on the plateau, the snow shimmering and sparkling in the sun, being in a place I’d always wanted to be, was the most wonderful feeling. ( Guess it’s about time for a Sound of Music theme song to start, but all sappiness aside, it really was wonderful to be there!)

Anyway. Excuse the digression into rhapsody, and on with the story. After a week, it was nearly time for the Losar (Tibetan New Year) holiday to begin, so the school kids left the monastery, where most of them were staying with monk relatives, to return home to

prepare for the celebrations.

C and I went off to visit his family, who live in villages near the town. First went to stay with his elder brother, the brother’s wife, and two daughters, as well as C’s father. Stayed there for a couple days, having great conversations with his father and two young nieces, technically named Dorje Tso and Pema Kyi, but who we promptly renamed “Hello and OK” after our attempts to teach them a few English phrases were returned by a determined repetition of those two words.

The thing about visiting Tibetan families, is that those families tend to be very very large. Over the space of the next week, we visited his grandmother, a marvellous old lady who burst into fits of laughter with no warning whatsoever, and who told wonderful stories, also interspersed by laughter. There were also various aunts, uncles, cousins, nephews and nieces, as well as neighbours who also wanted to get a glimpse of a real live foreigner! All the hospitality was great, the only downside being that I think I ate three months’ worth of food in the space of a few weeks. It is a typical Tibetan custom of course, to offer vast amounts of food to one’s guest, but this was magnified by it being Losar, so at each home we were greeted by a heaping plate of fried bread (kapsi), plates of dried fruit, fresh fruit, peanuts, sunflower seeds, biscuits and cup after cup of hot Amdo tea. After an half hour or so of chatting, these would be pushed aside to make way for an even larger plateful of large steaming chunks of boiled yak meat or pork, complete with bones and inches-thick fat. You eat these with a knife, sawing off bite-size chunks, until you’re stuffed, and them are persuaded to eat more, the family urging you to “Eat, eat! Is it not good?” When you’ve finally eaten so much that there is absolutely no way you can eat anymore, the plate of meat is moved to the side, and a large bowl of momos in soup is set before you! You can’t refuse with any amount of delicacy, they simply won’t take no for an answer, so after the first couple times, I got smart, and developed a strategy to eat tiny bites and very slowly, chatting away or listening keenly to the conversation, and keeping an eye on the housewife, so that each time she looked over at me, I made sure to be raising the tea to my lips, or cutting off a bit of meat. This didn’t fool all of them, but it did help!

I’ve been asked to describe what the houses are like. They are quite similar in setup, as far as I saw. From outside, they look like fortresses, with twelve foot high thick walls made out of clay mixed with straw and ash until it is rock hard. Once built, these walls can last for years. Each household has a large gate in this perimeter wall which can be locked at night. I asked why the walls were so high and thick, and was told that they serve many purposes. First to prevent theft, primarily in latter years of livestock. As the grazing gets more and more restricted, it has become more difficult to own large herds of sheep. As fewer people can afford to run sheep, the prices of sheep have skyrocketed, with each sheep costing upwards of 700yuan apiece. That’s about 100$ a sheep. So the herds are taken out to pasture in the day, and locked up at night. Also the walls create a windbreak. Homes have no central heating system, so the protection from the wind is important. A house typically has windows only facing inward into the courtyard within the walls, with some more modern homes having a small glassed in porch, which collect some of the sun’s afternoon warmth, even in the winter. Inside, each home has one large room where the family spends most of its time. Along one wall, usually on the right side of the house, is a large shelf-like bed, where the family sleeps at night. This shelf is ingeniously heated by a pipe which runs from the tiled hearth stove, where a large pot of hot water is continually bubbling, into an open area beneath the shelf. During the day, quilts and blankets are neatly folded into piles along the back wall, and will be pulled out at night. The hearth is where most of the cooking is done, with an open fireplace over which water is heated for tea. There are two large holes cut into the tiles of each hearth, into each is fitted a large pot, one for hot water, and the other for frying food. The fireplace continually needs to be tended, which is usually the chore of the women of the house. As there is very little firewood available in Tibet, most of the fuel is dried yak and sheep dung. All year, dung is collected, patted into pancake shapes, and slapped onto the outside walls to dry in the sun. Once dried, it doesn’t have an unpleasant odour, but burns fairly quickly, and the fire is always needing stoking. A few wealthier families had coal, or twigs and branches to burn, but everywhere I stayed, dung was still the most used. As well as the hearth, all homes had a cast iron stove, used for heating as well as cooking. These give off a pleasant warmth, and when a guest first arrives, they are usually ushered first to sit by the stove and given a steaming cup of hot tea. Along the back wall of each home, there are usually cabinets and shelves built into the wall, in which are kept the families’ clothing, dishes and other belongings. Also, incongruously, most homes have a TV, and occasionally even a DVD player. In one corner, there will be a table where the women do most of the cooking, alongside which is a large clay pot to hold water. Most homes where I stayed didn’t have running water in the home, though there was quite often a well with a pump in the courtyard or nearby. The walls of the homes are often of whitewashed clay, sometimes paneled with wood, and usually decorated with large brightly coloured posters of fruit, fat babies, luridly exaggerated waterfalls, or animals frolicking on meadows of a green that no natural meadow has ever been! The ceilings are wooden logs peeled of bark, with more slats of wood laid crosswise. In all village homes, though not in the monasteries, the main beam of the house will have a large red cloth tied to around the beam with a kadag. I asked about this, and was told that it is a tradition when the house is built to put some precious materials in the cloth, then have the carpenters tie it to the beam to bring good luck and prosperity to the home. Apparently the tradition goes that the carpenters first demand money, and are given gifts to tie the cloth to the beam. A way of ensuring a tip I suppose. The houses aren’t well lit, with usually just one bulb hanging near the hearth, with a long cord so whoever is tucked into the warmth of bed doesn’t have to leave the shelter of the blankets to switch off the light. Over the years, the smoke from the fire turns the ceiling beams a sooty black, and the rays from the window create a chiaroscuro-like effect that would have delighted Rembrandt with endless possibilities for paintings. Outside, the courtyards of the homes are swept scrupulously clean. There are usually other rooms in addition to the main living room. Sometimes there will be another room to sleep in, if the family is a large or wealthy one, and also a pantry of sorts to store the family’s food, things like butter, bags of harvested barley or wheat, and vegetables pickled in salt. Most families produce the majority of their own food, of necessity, as most farming families, with several working adults, won’t earn make much more than 1000 yuan profit a year. There is also a large neatly stacked pile of dried dung for fuel, and whatever farming tools the family owns.

Outside the compound, there may or may not be a “toilet”. If there is, it will be a slot cut in the ground, which one straddles, throwing a handful of ash down afterwards. Otherwise, it’s out to find a spot in the fields, which is probably fine in the summer, but in winter can be brutal, in the dead of night, with the icy wind whistling round one’s nether regions! And taking care of course, in your midnight dash for relief, to take the torch, so one can avoid the family guard dog, a large Tibetan mastiff which barks madly, hurling itself against the chain which is the only thing preventing it from bloodshed!

Well, that pretty much ends my description for then moment. It’s a bit hard to stop once started, but I suspect some of you may be falling asleep at this point. Nice thing about emails and letters is that you can put them down or turn them off when you’re bored! So I’ll consider myself turned off, and move on to a new topic…

So after the rounds of all the extended family in the various nearby villages, we next were invited to the family of C’s two nieces, who’d been living in the monastery for a few weeks to learn English, and had now returned home for Losar. So we passed through town, to what passes for a Tibetan subdivision (all the identical houses built in rows) to stay with their father, C’s father’s cousin (the Tibetan system is complex, what someone calls a cousin could actually be a second nephew twice removed!) and his family for a day before returning to the monastery. We went for a wander off up the hill to the nearby mani-khang, and to the poles strung with prayer flags blowing in the icy cold wind. The girls are a lot of fun, and we giggled and messed about in the snow, taking lots of silly pictures, before dashing back to the warmth of the fire indoors. We had to leave early the next morning to go back to the monastery, as C wanted to do some shopping for Losar first in the town, and it turned out that the girls had wanted to have their picture taken with me dressed up in Tibetan clothes, but had been too shy to ask, so they made me promise to stop by again on the way out when I left. This promise duly made, we set off, got the shopping done as quickly as possible, as the weather was getting steadily colder, and returned to Tharshul. With just a few days to go until Losar, we found out that a famous Geshe in Labrang had just died. He had been the main teacher of Tharshul, so several monks had gone off to Labrang for prayers. This meant that there would be no official Losar celebration out of respect, just quiet celebrating with friends at home. The morning of the New year, February 7th this year, all the monks were off to prayer early, so I had a bit of a lie in, then got dressed up in my Amdo gear to go off to offer kadags at the temple for the new year. When D and J T got back, we had a quick breakfast, then went off to the temple to do the offerings before prayer started again. After lunch, some of D’s relatives turned up, chatted for a while, then we went off for lunch to K’s house, and to watch, oddly enough, “Braveheart” dubbed in Amdo! It was quite amusing to watch Mel Gibson apparently spouting off a stream of broad Amdo dialect, but my amusement was not easily translatable! The next few days were a blur of food once again, invited out to various friends’ homes for lunches, brunches, dinners and suppers….When I get back to Chengdu, I’ll not have to eat for a month! On the 2nd day of Losar, (our 9th of February) I and C were invited to the abbot’s home for dinner. C had asked me to help paint the new debate ground in the summer. Their prayer hall had recently been painted within and without, but the chura had yet to be done. C, K and I had all worked on painting the prayer hall in Mundgod, so had some experience. He’d talked to the abbot, and the abbot had agreed, saying he’d hire one professional painter to come and do the planning, and then the rest of us would do the painting. So I’ve been offered a house to stay in this summer, and will spend two months painting, teaching English at night! Brilliant…now I can learn more of the traditional methods, as well as live in Tharshul in the summer with friends. So Losar passed quickly, eating, laughing, talking, playing cards, with the usual penalty of having a black mark painted on your face when you lost a hand…the 4th day, the first day of the Monlam prayers, and the day I was to leave came all too quickly. The afternoon of the 3rd, C and I went back to Rapgen to see the girls again and have the photos taken.

While we were there, a huge crowd began to gather outside to await the arrival of a new “namma” (bride) to a neighbour’s home. The village women kept dropping by to gossip and tell tales of past weddings, of the wedding clothes and jewelry worn, the amount spent, and to anticipate what the newly arrived bride would be like. Weddings in Amdo, particularly among the villagers and nomads have changed little over the years. The bride and groom usually don’t know each other, and often have never even seen one another. The groom’s family begin looking around for a potential daughter in law when he is in his late teens or early twenties, sending word out to friends to ask about for a good girl. When we were staying at C’s sister’s house, the main topic of discussion was a bride for her 17 year old son, as they were planning for him to marry this year. According to his mother, the girl should be hard working (most important), from a good family, never before married, humble and fairly good looking, among other things! The boy’s father had died a couple years ago, and his mother was concerned that he’d develop bad habits if he didn’t marry soon. The family discussed the boy and his future wife openly before him, and though I watched surreptitiously to see what his reactions were, his face didn’t display any emotion as far as I could tell. For us in the west, the prospect of an arranged marriage is unbelievable, in particular for the girls. In the homes I visited, it was clear that the “namma” was pretty much a slave in many ways. Once a girl has been chosen by the groom’s family, the bartering begins. The groom’s family has to literally buy the girl from her family. The clothing and jewelry she will wear to her wedding are bought by his family as well, so the bride price is the subject of months of discussion before everything is finally agreed upon. The girl herself has little or no choice in the matter, though some more modern families do allow their daughters to finish school first.

An auspicious day is chosen for the wedding, and the girl is dressed in her finest, and is loaded weeping into a car decorated with colourful scarves that flutter in the breeze as they drive away. With her are several female relatives, usually sisters or cousins, and several other carfuls of family and relatives will follow in a procession to the groom’s house, where his family have been preparing a huge feast for the wedding. The car stops at the edge of the village, and the women get out, the poor namma still weeping inconsolably behind them. She is supposed to cry all the way through the wedding day, to symbolize her sadness at leaving her home and family. As the proceed slowly down the path to her new home, the women sing songs, which are replied to by the men of the groom’s family. Finally they reach the gateway to her new in-laws’ house, and speeches are made, spirits are drunk, and she is formally welcomed to the home. At this point, I and the women of C’s family could no longer follow, as we and all the other women of the village had been doing, checking out the clothes and jewellery of the wedding party and thus fuelling the gossip of the next few days. We left reluctantly, back to the house to discuss the bride and compare her with others past and future! C and his uncle were waiting back at the house, as monks take no part in such events. We spent a sociable evening, then rose early the next morning when the epic of trying to get on a bus back Xining started. His family told us not to bother going back to town to the station, as the bus would pass right by the village, so we waited in the bitter cold out by the road along with a group of other people, until the bus passed. Passed….it was full. It wouldn’t ordinarily have been a problem, but Menba had driven to Xining and was waiting to pick me up, so I had to arrive that day. As it was a 5 hour drive, we had the option of waiting for the “next” bus, which noone was really sure existed (though there were many vociferously stated differing opinions on the topic!) or going to town, and trying to arrange a car. This seemed to me the best and obvious option, but turned out to be easier said than done, as there was little traffic in either direction, apart from processions with “nammas” heading to their prospective new homes. It was the fourth day of Losar, an auspicious day for such travel, but less auspicious if one happened to be wanting a bus to Xining instead of marriage! Eventually did get a lift, and arrived at the station only to find that the next bus wasn’t until the next day, and several other buses going to nearby towns, from which I’d have to transfer, wouldn’t leave for several hours. Option number two was to look for a private car heading to Xining, which was more expensive, but there being a serious shortage of other options, was the only way. This was duly accomplished, and I and my pack were loaded into a carful of Muslims going to Xining. So off I went, a hundred yuan poorer, but at least going to arrive in time to meet Menba. The driver chainsmoked and sped the entire way, and we arrived a couple hours sooner than I would have on the bus. Apart from the smoke (the one really bad thing about travel in this part of the world is how many people smoke, especially on public transportation) it was a beautiful drive, over the mountains and grassland, past nomad settlements and back to the city. There I was met by Menba and his brother in law, who had his own car, and after a quick lunch, we drove off in style on the hour-long drive to Jianza.

Part 3 Jianza, a visit to Labrang and Geshe S’s village

Arrived in Jianza that evening, and went to stay with Menba’s sister’s family in a village perched on a hillside, with roads just barely the width of a car. The family had been awaiting our arrival and came rushing out to meet us. The next hour or so was of course spent in eating yet more food…the next day, we drove up to his monastery, and I saw the little hospital he is now running, then drove out to Machu river, where a small motor boat took us out across the river to the Kambala nature reserve, a vast area of oddly shaped cliffs and canyons. The mountains had been eroded over the centuries by wind and snow, and reshaped by landslides into weird spikes and overhangs. Pockmarked by caves, some of the cliff surface looked like melted candlewax. The river flowing down the canyon floor to the Machu river had frozen solid, but was so clear one could gaze down into the green depths. The boatman let Menba and I off after pushing through broken chunks of ice as far as the edge of the ice shelf, and promised to return that evening at 5 to pick us up. As he slowly dragged his boat back out through the ice floes, Menba and I gingerly picked our way up the river, slipping and sliding on the ice. Trying to simultaneously walk on ice without falling and still look around at the magnificent scenery around me was a feat in itself, but I did manage to pause now an then in the ascent to take a few photos. The stillness was absolute, the air bitterly cold, and the sky wintry white against the red of the cliffs. Higher and higher we climbed, gasping in the thin air. I had wrapped my scarf around the lower part of my face, and my breath had frozen the patch in front of my mouth to a chunk of ice which banged against my face as I climbed. Eventually, we reached a narrow trail along the cliff edge, which led to a Nyingma nunnery. Completely isolated in the winter, there was a road away through the mountains, but that was only accessible in the summer months once the snow had melted in the passes. Goats leapt nimbly out of our way as we staggered up the trail, trying to suck as much oxygen out of the thin air as possible. Finally, we arrived at a series of chortens, and the beginning of the steep paths wending their way through the nuns’ residences to the prayer hall. It was a large nunnery, with several hundred nuns living there, and as we arrived, we followed the sound of singing to the temple courtyard, where the nuns were celebrating Losar by singing along to taped music. As we approached, and they saw that a monk and a foreigner had turned up out of nowhere, they quickly switched off the tape player in shyness and confusion. But after we’d been quickly ushered into the kitchen for a steaming cup of tea and chunks of dry Amdo bread, they started the music up again and carried on their singing. I peered out the steamy windows to watch, while Menba chatted with some of the nuns he knew. On the bed-shelf beside the fire, a group of nuns were making tormah ( sculptures made of tsampa and butter, coloured with red dye) for the coming New Year and Monlam prayers. Sitting on chunks of wood beside the fire, bowl of tea warming frozen fingers, we laughed and chatted with the nuns, until finally, I crept quietly outside for a while to watch the singers again. By this time, word had spread that I spoke Tibetan, and they were less shy. Much less…they wanted me to sing! I quickly convinced Menba to leave, and go look around the nunnery. Several of the nuns accompanied us, opening the prayer hall so we could go and have a look around. Much of the nunnery buildings had obviously been newly built or renovated, and the thangka paintings inside were brightly coloured and beautifully done. After a quick tour round, we went up to visit a nun relative of Menba’s, for yet another cup of tea, before heading back down again for lunch in another nun’s room. The hours sped by, and when we next checked the time, it turned out to be too late to continue up the track to visit the monastery farther up the canyon, and still have time to get back to meet the boat at 5pm. The nuns were eager to have us stay for the night, but as we’d plans to go to Labrang early the next morning, we regretfully turned the invitation down, and headed back down the path to the frozen river, finally reaching the waiting boat. The trip back across Machu river was perhaps the coldest half hour I have ever spent in my life. The wind was against us, and though we huddled deep into our hoods, and wrapped scarves around our faces, covering all bu s slit for the eyes, the icy wind seemed to creep into every inch of our bodies, and we clambered stiffly out onto the shore on the other side, numb and shivering. Menba’s brother in law was waiting in the car with the heater turned up full blast. We slowly defrosted on the drive back home, and were greeted by large plates of hot chunks of meat and momo soup.

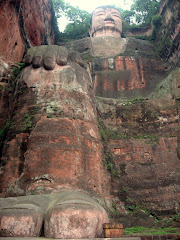

Early the next morning, we drove back up to Menba’s monastery, to pick up the lama who was to be taken to Labrang. He is the reincarnation of the previous monastery abbot, now aged 14, and was to go live and study at Labrang for 10 years before returning to the monastery here to take up the position of abbot himself. Everyone was concerned about the weather reports, as it was said to have been snowing on the passes on the way to Labrang. Nevertheless, we set off on the 4 hour drive, with promises to drive carefully. Menba and his brother sat up front, while the lama, his mentor and I were crowded in the back seat. I spent most of the trip gazing out the windows of course, as we drove along virtually abandoned roads to Rapgong district, renowned for its artists. As we drove through one village, the monks told me that the people in that area were called the “lice-eaters”, which they swore was true, and not just rumour. As we drove, the landscape changed from rolling hills and terraced farmland to deep gorges with towering cliffs on either side. The road perched precariously on the side of the cliffs followed the serpentine river, frozen into smooth glassy green in some parts, and frothy snow in others. One large smoothed areas of the cliffs had been painted Tibetan symbols and words. Once as we emerged from a sharp turn, we gazed up in awe at a huge colourful Kalachakra symbol etched into the rock. A few kilometers later, there was a huge relief Buddha, serene among colourful clouds and banners. At the foot of the cliff, was a small shrine covered in prayer flags and kadags. As the road continued through the gorge, the sides of the mountains became dotted in evergreen trees. At a fork in the road, we turned left, while the road to Rapgong town lay to the right. If time and weather permitted, we planned to stop on the way back, to check out the famous thangka paintings at Rapgong monastery.

From then on, the road grew steeper, as we climbed higher into the mountains. The higher we got, the worse the road became, and it began to snow. On the left, the cliff rose steeply, blocking out the sun, and snowdrifts had piled up at the base. Rocks littered the road surface, chunks having cracked and slid down the cliff, making the narrow road, already have its original width because of the drifting, even more difficult to negotiate. On the right, the shoulder of the road was a breathtaking drop into the river gorge. The driver was muttering prayers, Menba was singing loudly and off key along with the radio, occasionally breaking off to exclaim at some barely passable stretch of road. The lama was asleep, nodding off against his mentor’s shoulder, and I was carefully NOT looking over the edge of the gorge, and praying that no traffic would come the other way. When a vehicle did appear, both drivers would slow to a crawl, and inch their way past each other. Finally, a tense hour or so later, we inched over the pass, and gazed awestruck through a haze of snow over the vast grassland and hills stretched before us. The road down the other side of the pass was just as bad, covered with snow and ice, and with no guardrails to prevent us from slipping over the side of the road. Slowly we drove, passing several accidents, where vehicles had obviously slid into one another. Pausing for a quick stop at Garze town, we were told that the road would be much the same for the rest of the trip, and to proceed with caution. So we carried on, leaving quickly so as to arrive well before it began to get dark. Garze has a large monastery with a large mani wheel kora around it, but we hadn’t time to stop and look around, as the driver wanted to get to Labrang. The road was still slippery and covered in snow as we drove up and over the hills, passing settlements of nomads and their herds of yak and sheep dotting the hillsides. As we neared the Labrang area, the snow got worse, until we were driving nearly blind, but as we were out in absolute wilderness, there was nothing for it but to carry on. Finally, after an exhausting 5 hours, we reached Xiahe, a modern town with restaurants, hotels and tourist souvenir shops selling everything from prayer flags to monks’ robes.

Stopped for lunch, before carrying on down the street past the mani kora to the monastery and the lama’s residence. We were fed again there, of course, and rested for a short while before setting off to explore. The lama immediately sat himself in front of the TV, the driver settled down for a nap, and Menba and I went out to wander around the monastery. He hadn’t been there since he was young, and it was my first visit, so we started off around the mani circuit, taking photos of each other like a couple of tourists. I called Jinpa, the Labrang monk I knew from Chengdu. He’d written a tour guide book of Labrang, illustrated with beautiful photos, which he’d asked me to edit, so I was looking forward to seeing the result. He stopped by and invited me to his room for tea, and gave me a copy of the finished book. We chatted for a while, and he volunteered to take us round the monastery the following day. I was also supposed to meet K, a relative of a Tibetan I’d met in the States, as I’d been given some money for the family. With great difficulty, Jinpa helped me locate K, and finally I was able to hand over the money I’d been carrying for months. I really don’t like carrying other people’s money, and it was a great relief to hand it over. We made arrangements to stop by their family’s home for lunch the next day before we left again for Jianza. Early the next morning, Jinpa met us, and we were taken on a tour of Labrang. As it was still snowing, we had only the morning, as the driver wanted to leave by noon to get back over the pass when it was still light. So we did a whirlwind trip of various temples and ladangs, had a look into the museum, to marvel at an eclectic collection of oddities such as old wooden guns, armour, ancient texts printed in gold, and a “horse horn”! Having Jinpa as a guide meant that everything was opened for us, though most temples were closed for Monlam prayers. As we walked around, there was a teaching being given, and any senior monks were going to the temple for it, dressed in their Monlam finery. Labrang was also crowded with pilgrims, and I longed to take more photos of sun darkened wrinkled faces and the traditional clothes of some of the elderly women. However, I can never bring myself to obviously take pictures of people, so spent some time trying to surreptitiously

lurk in the background, whipping my camera up and clicking before I could be spotted. There were no other foreigners as far as I could see, though there were many Chinese tourists with long lensed cameras taking all the pictures I didn’t have the nerve to take myself! After the tour, we met back at the lading, and set off for lunch at K’s family’s home. It was a quick affair of smoky tea, the inevitable chunks of boiled meat, and a delicious dish of the little “bug fungus” with rice and sugar. Took a couple of quick photos to send their family in the US, then set off, the driver impatient to be on his way out of the mountains before the snow got any worse. The trip back was pretty much the same as the one up, with the car immediately ahead of getting into an accident, as well as the one behind slipping off the road into the cliff. Noone was injured seriously in either, but we were unable to stop, as when we tried, the first time to see if anyone needed help, we had a really difficult time getting traction to carry on up the hill. I’ll not bore you by repetition of the drive back, as it was just as life-threatening as the way in. Suffice it to say that we decided not to stop at either Garze or Repgong on the way back, and rather to carry on down into the relatively low land of Jianza. We reached Jianza town late in the afternoon, and made a short detour to visit Gen L G, who had been ill with hepatitis, and had recently had an operation to remove his pancreas, from which he was now recovering. Gen L G was a famous teacher in Gomang, with several thousand students, and is renowned for his knowledge of Buddhist philosophy and his ability as a teacher. He had been requested to return to Amdo, but shortly after he got back, had fallen ill. He had been close to death, unable to walk or talk, but when we saw him, he looked better, though thin and yellow from jaundice, and was able to speak and get up. We only stayed for a short time, so as not to tire him, and then returned to Menba’s family’s home. The next day I was supposed to go to meet C, but it turned out he was unable to come, as he had some work in his monastery for his brother, a high lama. So instead, after staying the night in Menba’s flat in town, we left early in the morning for his monastery where he tended to patients, while I wandered around, chatting to some villagers grinding tsampa, and taking photos. That afternoon, we drove to Geshe S’s village, about an hour from Jianza town, but up yet another road from hell. Not because of the snow this time, but because summer landslides had swept most of the road down the side of the mountain, so that in many places we were driving on a bumpy patch of dirt carved slant-wise into the side of the cliff, while the left side of the road disappeared into the valley, a mass of rock and frozen mud clinging to the side of the cliff. At one point, a bridge had been washed away, and a precarious track of dirt had been cut into the side of the mountain, with the asphalt of the road suspended over nothingness. As we edged onto this, with the right wheels on the dirt, and the left side wheels on asphalt under which I knew there was nothing but a long drop, I had the sudden urge to take a photo of the experience, but restrained myself, knowing that extra seconds on the platform of unsupported asphalt would perhaps not be in anyone’s best interests who desired to live a long and healthy life! So it continued, the road turning eventually into a rough track, and branching off in various directions without any form of signage whatsoever. Nonetheless, the driver seemed to know where he was going, and drove along carelessly, talking on his cell phone the whole time. We arrived intact at S’s village, and his whole clan turned up to meet us. His mother was a tiny, nut-brown wrinkled woman with a lively sense of humour, and gnarled hands, that clutched mine as we toiled up the steep path to their home. Various aunts, uncles, cousins, and other relatives all piled into the house to check out the visitors, and to be checked by Menba. After an hour or so, Menba and the driver headed back down to Jianza, and I stayed to be fussed over by the women, and to be fed yet more plates of meat and momos. The next day, S, his brother in law and I went out for a walk I the hills overlooking the village, to attempt to walk off some of the huge quantities of food we had eaten. Upon returning home, we were invited out to another relative’s home, for yes,

more food. I have eaten three months’ worth of food in the space of a few weeks, I think.

Going hungry is never an issue, when one lives with Tibetans. Gaining unseemly weight is a problem however!

The following day, the 16th, I had to return to Xining, as my train ticket back had been booked for the 18th, and I wanted to make a trip to Kubum and to see the Great Thangka before I headed back south to Chengdu. So bidding farewell to S’s family, who were insistent that should return in the summer, I was loaded into a taxi and sent off to Jianza under the care of S’s brother, who was to see I got safely on the bus to Xining. In fact, the whole 6 weeks of my trip has been a bit like being a parcel sent back and forth to various monks. Loaded into one bus, and picked up at the other end and taken somewhere to be fed, it has been one of the easiest trips I’ve ever made. Most people with any sense at all don’t travel to Amdo in the winter, but despite the cold it has been an amazing trip, and brilliant to meet up with so many friends again.

Part 4 Xining again : Kubum and the Great Thangka

Arrived back in Xining, and was picked up by R at the station, with a backpack even heavier than when I’d left. I had tried to lighten the load, by leaving my Amdo chuba, sleeping bag and boots in Tharshul, rather than carry them back to Chengdu where I’d no use for them, but S’s family had given me a load of tsampa, chura and yak butter, as well as one of the large, heavy wheels of Amdo bread, several kgs in itself!

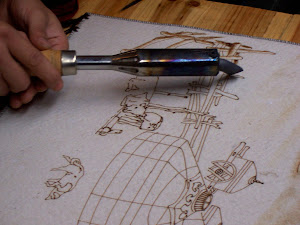

(A veritable sample of dwarf bread, for any of you who know your Terry Pratchett!) We went back to her brother’s flat, where I had stayed on my first arrival in Xining, and spent that night chatting with her mother and two young nephews. The next day, we went early in the morning to Kubum, to visit G D, and to have a look round another of the most famous Tibetan monasteries. Kubum is the Dalai Lama’s monastery, and isn’t far from his birthplace of Taktser. Rinchen Tso and I waited by the eight chortens at the monastery entrance, and when G D appeared, he took us on a whirlwind tour of the many temples and ladangs of the monastery. Kubum is in a much better state of repair than Labrang, as its renovations have been largely funded by China. The temples were full of gold statues and ornate decorations, but the monastery itself has no study of philosophy, and the debate ground is no longer used. I’d have taken many more photos that I did, but my camera’s memory card was full, a terrible situation for any tourist, so when GDmanaged to get us into the private rooms where the huge butter sculptures were being made for the display on the 15th day of Monlam, I desperately cleared off a few other photos I had taken! Kubum’s butter sculptures are famous throughout Tibet for their intricacy and size. Normally one is not allowed to see them until they are complete and on display, but the crowds on the day of the 15th are prohibitive, so we were fortunate to have the chance to see them in creation. Went back to G D’s room for lunch, then headed back into Xining to catch a bus for the Great Thangka museum. This is something I had wanted to see for sure when I was in Xining, as it’s one of the most amazing works of art I have ever seen. It is the longest thangka in the world, stretching an amazing 618 metres long, 2.5 metres wide, and weighs 1000 kgs. It took more than 300 artists over 4 years to paint, and is said to contain all of Tibet’s history in one work of art. (I include this information from the Great Thangka website)

“The Great Thangka includes information on the world's formation, human creation, Tibetan origins, Tibetan monarchs, Sakyamuni’s biography, the origin and development of Tibetan Buddhist sects, the sciences of linguistics, technology, philosophy, medicine, astronomy, poetry, rhetoric, and drama, the Tibetan architect Thangtong Gyelpo’s condensed biography, a condensed version of the Tibetan epic 'King Gesar', Tibetan scenic and historical sites, seven wise ministers and seven strategic generals in Tibetan h i s t o r y, f e s t i v a l s and clothing, daily necessities, weapons, houses, tents, castles patterns including the eight auspicious symbols, and pictures beseeching luck and fortune.

The newly created versions of Tibetan landscapes in the Great Thangka combine Tibetan and modern painting techniques, offering viewers a fresh interpretation of the familiar. There are 300 images of 30 palaces in minute form in this Thangka. In some places, a 1/30th square meter holds 2,480 pictures, which is only possible to paint with a very small soft-hair writing brush, and many other squares include many miniature pictures visible only with magnifier.”

R and I wandered around the museum, which on its first floor had a selection of old medical thangkas, and ancient Tibetan medical instruments, many of which looked more like tools of torture than of medical or surgical use. The thankga was upstairs on the second floor, and it took us several hours to see all of it. It would take many more than one visit to really have a good look at every part of it, but after looking fairly closely at the details of the first half, one’s mind becomes so full of detail that you can’t take in anymore. Besides, R not being an artist, I thought she’d be getting bored by it all, so we walked more quickly past the second half, just as well it turned out, as the museum was waiting for us to leave so it could close. Back home on the bus, picked up my train ticket, only to discover that it left at the unearthly hour of 8:15am, meaning an early wake up and trip to the station. R went with me, bless her, loaded me an my heavy pack on the train, and then returned home. I slept for much of the trip back, full of mixed feelings about leaving. The school in Santai is good, the teachers and students friendly, and I have to admit, it was going to be nice to get back to a washing machine and a hot shower, but I was also sad to be leaving what I really felt to be home. It had been so nice to meet up with old friends, be able to communicate without difficulty, and to visit a place I ‘d been hearing about for the past 10 years. So I was glad to be going back, but sad to leave all at once. Arrived back in Chengdu, to a sky full of smog, and no sun in sight, and it was hard not to recall the blue clear skies of Amdo as I pushed my way through the throngs of people in the station, and got in a taxi for the hostel. As we arrived in the Tibetan area of the city, it was good to relieve my beginning withdrawal symptoms by the sight of monks and Tibetans in traditional clothes bustling about the streets. First matter of importance was a hot shower, to scrape off some of the accumulated grime of the past weeks. (I’d had four showers in 6 weeks, and was feeling decidedly grubby!) then I headed out onto the street to look for something to eat. As I wandered around the Tibetan quarter, I noticed a monk looking at my quite fixedly. This is not so unusual, as many haven’t seen foreigners before, but he looked familiar as well, though I couldn’t place him. I didn’t want to say anything, in case I was wrong, and started to walk away. He and his friend started to walk away as well, but when I looked back, he was also looking back at me. I went into the next shop, and when I turned to come out, he was waiting. “Tenzin Dolma?” He asked, and it turned out he was a Mundgod monk from Litang. We arranged to meet up later, and I decided to stay an extra night before heading back to school. Spent the next morning chatting and catching up on gossip, until it came time to return to the hostel. On the way back, I saw another monk, who looked awfully familiar, and it turned out to be another monk friend, in town for a few days. So it was nice to have my passage back into the reality of my life at school eased by meeting up with more old friends. Now I’m writing all this back at school, classes begin tomorrow, and I have to get back into “school mar’m” mode for the three months left of my contract. However, three months goes quickly, then it’ll be summer holidays, and I can head north to travel again! For those of you who have managed to read this epic to the end, I salute your perseverance, and hope you’ve not been bored stiff!

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment