Chengdu to Xining

After 2 years spent in Sichuan, waiting for the time and circumstances to be right to move up here, it finally happened this summer. I cheerfully handed in my resignation and the final weeks of my time in Santai were spent packing and shipping off most of my stuff to Xining, and getting ready to head off for a month’s holiday in Laos and Thailand. I had to return in time to begin classes in Xining on July 15th, so crossed the border back into China about 10 days early, so as to make the trip north overland, via Ngawa, Childri and Gabde, stopping to visit friends on the way. Unfortunately, the weather was abysmal, raining or overcast and chilly for most of the time.

Upon arrival in Xining, I stayed with a friend for the first weeks, while looking for a flat to rent near the office. Found one easily enough, but had to wait a few weeks until the two American women students living there moved out.

My Flat

The flat is nice, for the most part. It’s on a quiet lane connecting two bigger roads, and is shaded by willow trees. The apartment complex is actually housing for teachers/staff of the Tibetan Medical College, so all my neighbours either work in the school or are retired. The flat itself is on the ground floor (finally defeating my previous belief that all foreigners living in China had flats on the 5th floor or higher, a fact carefully researched among friends in Sichuan) It has 2 bedrooms, a sitting room a kitchen, entranceway with pantry and sink for washing up and a bathroom complete with hot water heater. The bathroom is the only real source of my complaints…as with most flats in China, the pipes occasionally give off a foul smell. I suspect the drainage systems are not the greatest, especially with so many people using them. So I go through lots of incense and air fresheners. Also, this flat has some great eccentricities. The best one, in my opinion, is that there was a water heater installed for the foreigners (who, oddly enough, seem to insist on taking hot showers…!) however, there’s not actually a drain. So there’s nowhere for the water to go. I purchased a large blue bucket, and now take my showers standing in it, getting out once or twice to dump the accumulated water down the toilet! Ah well, at least there is hot water, and plenty of it. The second day after I’d moved in, however, a vast lake of water suddenly appeared in the entranceway, and flowed into my bedroom as well. This fortunately was not from the toilet, but from the pipes leading down to the sewers from the sinks. Something down in the pipe below the building was blocked apparently, and as people on the higher floors used their sinks the water, having no other place to go, overflowed into my flat. When one doesn’t speak Chinese, it makes it exceedingly difficult to communicate in a hurry. A monk friend was staying with me at the time, and his Chinese was not much better than mine. Nevertheless, he dashed off to try to find a plumber of some description, while I went upstairs banging on doors, telling the half awake people who opened the doors “Water, water (one of the few words I know in Chinese!) and making wild gestures to attempt to convey the fact that my flat was flooded and please for them not to use their sinks. After some baffled looks, they finally seemed to understand, and I went back down to mop up the inches deep water. This happened for two days in a row, and I have to admit the novelty and amusement factor wore off rather quickly. However, the problem was remedied eventually by means of opening the manhole cover opposite the flat, and poking around with a long stick. Nothing like technology to solve one’s difficulties.

Walking to work:

My flat is near the office, only a 20-25 minute walk, which I do each morning and evening. Now that winter has set in in earnest, I bundle myself up against the biting wind, and stride off purposefully down the little road outside the compound gates, take my life in my hands to cross two main roads, and Xining Square. Crossing the Square is always entertaining, as the Chinese health freaks are all out in force, despite the bitter wind. There are kite-flyers, birdsellers, others walking energetically backwards and yet others who stand and shout into the wind ( to exercise the lungs?) There are also a few old men who carry buckets of water and large paintbrushes on poles and painstakingly write poetry in Chinese calligraphy in water on the stone slabs in the center of the square. As well, there are several groups that meet to do calisthenics cum line dancing to the music blaring from huge amps on trolleys. The fashion sense of these fitness addicts leaves something to be desired however. I myself am not exactly a walking fashion plate, but at least my colours tend to match, and I have never in my life tried to do jumping jacks in high heels. Never. Mind you, the women seem to live in high heels, despite the risk to life and limb. A few days ago there was a couple inches of wet snow on the ground, and the beautiful, but treacherous fired red clay tiles used to decorate the sidewalks, are a death-wish when it either rains or snows. I was wearing my clunky black shoes with treads, and finding it hard not to fall flat on my face, and these women were picking and wobbling their way in heels? Just one more thing I really don’t understand…But I digress. In addition to the aerobics groups, there are the sword dancers, and the tai chi practitioners, the occasional jogger, and the grandparents hauling wailing children off to school.

Another unique thing about this country is the road construction. This seems to be a permanent fixture in the city. When I arrived, the road was under construction, all piles of sticky mud and blocked off for traffic and leaving dirty passageways for intrepid pedestrians to make their way through the mess. Potholes were left uncovered, so you need to walk along with eyes glued to the ground, lest you vanish into the sewers of Xining, never to be seen again. Apparently, this was in aid of water pipes or some such thing. Finally, the surface was patched together, carefully repaved with the addition of the aforementioned dangerous red tiles, and we all breathed a sigh of relief. This last just over two weeks. Then the sidewalk was torn up –again- so a pretty garden strip complete with picket fence (which requires daily polishing to remove the layers of grime) could be added. Grass was planted, flowers and shrubs put in, and the whole thing was lovely once complete. For another 2 weeks. THEN all the carefully planted grass was dug up again to do something connected with the electricity poles. I am waiting with bated breath to see what will be dug up next and why…at least it’s one way to keep the population employed, but surely it’s a rather expensive option? What about the villages that don’t have proper garbage disposal, sewers or electricity?

Trace and teaching

Teaching the staff of Trace NGO is about as different as it could possibly be from teaching in the Chinese highschool in Sichuan. For a start, My largest class here is 9, as apposed to about 100 in Santai. I find that as a teacher it is a good thing if you can actually see the students at the back of the classroom. Also, the students here are really interested in learning. And I mean learning, not just passing exams. Obviously they need the language skills for their job, but these students even ask for extra work…unheard of! The students are divided into 3 classes, advanced, intermediate and beginner.

The beginner class is the drivers, and they are seriously fun to teach. They’re progressing in leaps and bounds, especially in speaking.

The intermediate class has also improved remarkably, especially considering that I only teach three days a week Wednesday - Friday. In that class, we’re working on pronunciation and speaking as well as grammar and writing skills. This class too is fun, and we laugh a lot, always a good sign.

The largest class is the advanced group, with 9 students. This lot has learned a lot of grammar, and mostly needs work on finessing writing skills, and in speaking/pronunciation. In this class, we study topics rather than grammar units. I began with a section on Michael Jackson, as he had conveniently just died around that time. I showed a few of his videos, and we discussed his life and the controversy surrounding him. We decided that most of the decisions he had made in life were to try to escape his background, and that he’d not really been successful at least not emotionally. We also discussed changing one’s appearance, how and why one would do so. From there, we moved on to Martin Luther King’s life, comparing how the two men had dealt with issues that shaped their lives, in what ways they were similar, and how different. I copied the I Have a Dream speech, dividing it into sections and assigned each to a student, asking them to “teach” the class their part. We discussed Rosa Parks, racism, discrimination and segregation, and I made a powerpoint showing photos of MLK’s life and the segregation in the USA. From that, we moved on to the history of slavery, and I showed another powerpoint of pics showing the slave ships and the situation of slaves in the southern states. Next we studied the Underground Railroad, and each student was assigned a person who’d been involved, such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, to research, and write an essay on. As summary of the unit on racial discrimination, I showed the movie “To Kill A Mockingbird” after giving the students a page synopsis and questions to be discussed afterwards. They really enjoyed that, and as a result, we’ve started a monthly movie night. Last night was the first of these. The students came to my place on Friday evening, and we watched “The Kite Runner”, again after me first giving them a paper with plot summary and questions to be discussed. The next subject is Obama, as a sort of result of years of fighting discrimination. We looked at his life, and discussed the ongoing controversy regarding his being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. We looked at the conditions of the prize, world reaction and talked about whether he ought to give it back or not. We will be discussing his views on issues, in particular Iraq and Afghanistan. From that, I plan to move on to discrimination by the Taliban, and from there to RAWA and women’s treatment/rights…It’s interesting to teach this class, as I have to do a lot of research myself in order to prepare.

Friends

One of the nicest things about the move here, is having so many friends nearby and passing through. Padma Reypa stayed with me for about a month when I first got the flat, then Choezin spent a couple weeks, and Gedun Lekshey came by for a few days. The gate guards, however were less than impressed that suddenly lots of monks were turning up in the flat compound. Monks and foreigners are both “sensitive” here, so both together are a recipe for disaster apparently. So I no longer have monk guests, but catch the bus down to the Tibetan market near the bus station to hang out with them when they come. Still, I manage to meet lots of friends here, and those not in the monk or foreigner categories come to visit me often.

As well, living in Xining means travelling to visit friends isn’t the mission it used to be when I had to travel north from Chengdu. When Padma Reypa was here, we went on a trip to Labrang, Repgong and Wendu. I also went to Henan to see the horse racing/archery festival and to visit friends and I’m plotting several more trips to see friends in the next weeks, weather permitting.

Projects and plans…

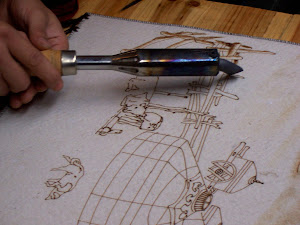

Now that I’m here, I can finally get to work on several of the projects I’ve been wanting to start for the last couple years. First is the art book. This is to be, if all goes well, the first of a series of four. The one I’m working on now is a book to teach how to draw realistic style portraits and people. It is to be all black and white, and written in Tibetan, Chinese and English. The plan is to have it published in January, and the last weeks have been a mad rush of trying to get all the drawings done, the text written and translated, and with trips to the printers to discuss paper, format and price. The idea is to start with printing 5000 books, and then go from there. Now that the deadline is drawing nearer, it is getting exciting, and scary… Dependent on the success of this first one, we plan to do next a book teaching how to draw animals, the third landscape, and the fourth and final book on perspective and drawing buildings.

Project number two, related and semi-dependant on project 1 is to start a small art school. This is rather more complex…but the general plan is to teach Tibetan, western and Chinese art styles. The main focus is to be on thangka painting, with 3 days a week devoted to that, then three mornings for western art and the remaining three afternoons for traditional Chinese painting. Students who complete the course, will be trained in all three styles, and as such, should have no trouble at all in finding work. This is important, as so many students complete school and then can’t find a job. Hopefully this will help at least a few to find viable careers and a way to earn for their futures. This project is very dependant on external factors, however, especially the political climate, so it is on hold until after March next year to see how things evolve.

Just to keep myself from getting bored, or ending up with free time of any flavour, I also am hoping to write another phrase book, as a step up from the first one, which has been really popular and has sold over 50,000 copies between India and Tibet. I have some changes in mind that I’d like to make, stuff I want to add/delete…

Hanging out with the clever people…

In October, I was invited to attend a 2-day conference of famous Tibetan scholars: authors, teachers, musicians and university headmasters. The topic was preservation of culture, and it was fascinating to listen to a gathering of great minds, most of whom are involved in various projects of their own to maintain their language and cultural roots discuss changes and options. I was the only foreigner present, and as such attracted attention. I was able to discuss my own plans with several of these people: Khenpo Tsultrim Lode, Rabgya Jigme Gyaltsen, Tulku Hunkor Dorje, Aku Lobsang, Tibetan author/teacher at Rabgya school. One of the best things about the conference was the evening informal get-togethers where people interested in similar projects met for tea/dinner to carry on talk and exchange contact information. Through this I was able and lucky to meet some very influential members of the Tibetan erudite community.

Writing all this, I am realizing how much has happened since arriving here, and how much I’ve not written. Typical, is it not, that when I had lots of time to write, I didn’t have much to write about. Now that so much is happening, and inevitably, it all seems to be happening at once, I can’t keep up. So for those of you who have been suffering through all the epics, be comforted that they will at least be abbreviated from now on!

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Trip to Amdo, Winter 2009

Ngawa (Aba in Chinese)

I’d been counting down the days to the winter holiday since my return from Thailand, and the last few weeks sped by, mostly because Tsokyi, a friend of mine from Ngawa had been staying with me. The last day of school came quickly, and on the Friday of the second week in December, I taught my last tow classes, finishing at noon, and Tsokyi and I were on the bus heading for Chengdu after a hasty lunch and grabbing our bags, which were all packed and ready to go to night before. Spent one night in Chengdu, meeting up with friends and doing some last minute shopping, before heading to the northeastern part of the city to he bus station which serves the Tibetan areas of Sichuan. There, we found out that there were no buses. Period. It was ironic really, only a few days before, the area had been officially “opened” for foreigners, after having been closed since March, but though “open” there were no buses running. Tsokyi and I asked around though, chatting to some of the Tibetans there, and they said there was a sort of taxi service, which left early in the morning. These were private cars, whose drivers had seen a way to make some cash. It wasn’t cheap, 220 yuan from Chengdu to Ngawa town. The train to Xining from Chengdu, much farther away, was only 170. However, there wasn’t exactly an abundance of options, so we decided to go. Part of the service was to book us into a nearby hotel, cheap, and near the station, where the owner would take us to the station in time to meet the driver, as we were to leave at 6am. This seemed a sensible idea, so we had a quick dinner at a roadside stall, feasting on a Chinese sort of kebab. One could choose from about 20 different baskets of meat, tofu or vegetables on wooden sticks, and these were deep-fried and served with bowls of super hot chilli sauce. Turned in early, since there was very little to see or do around the station, and it would be a long trip the next day. Leaving at 6am, we expected to arrive early evening. It used to be a lot faster apparently, but the road went through the earthquake affected regions, through Wenchuan town, and in many areas was still badly damaged. So off we went early the following morning. It was still dark when we left, but there wasn’t much to see until we escaped the outskirts fo the city, and started to head up into the foothills. After an hour or so, we reached some of the areas badly damaged by the earthquake. Lots of collapsed farmhouses, tiles scattered on the ground, and people living in makeshift shelters or tents made with heavy tarps. It’ll be a long, cold winter for them. In many places the road, or what was left of it, was a jigsaw puzzle of cracks and holes. In some areas there was no road, it was still buried under half a mountainside! There had been many avalanches, and the cars had just created temporary tracks veering around the buried sections of road. We drove slowly through the town of Wenchuan, one of the towns that had been worst affected by the quakes. The poorer suburbs of the town were still and expanse of rubble, with piles of cement and stone left in place of what had been homes. Apartment building were half collapsed, so you could see into what had been peoples’ homes. But in the centre of town, most of the better quality buildings, including the government buildings, police station and several newer hotels and shops looked intact, though many buildings had cracks and fallen plaster. I’d hear many rumours that most of the damage and deaths had been caused by sub-standard buildings, and from our brief drive through, it looked to be true. Not far out of Wenchuan, we entered the Tibetan area of Sichuan, obvious by the style of homes and the prayer flags on the hills. My heart lifted, it was like coming home!

Tsokyi slept in the front seat, while I gazed out the window. Most of the houses in the eastern part of the Tibetan areas looked similar to those I’d seen in the Lhagong area, built solidly of stone, window frames colourfully painted with traditional designs. Herds of yak and sheep dotted the hillsides, and the passes had chortens and prayer flags alongside the road. Our driver had a stack of printed lungda papers, which he handed us to toss out the window as we crossed the passes, shouting Lha Gya lo as the colured papers soared away on the wind. Tsokyi, bless her, had started to get really carsick as we sped around the serpentine bends of the mountain road. We had stopped once for a quick breakfast, but the driver was on a serious mission, and sped along, singing along with folk songs on the radio at the top of his lungs. Around 1 in the afternoon, we reached the town of Ngawa, called Aba by the Chinese. The other passengers were shocked, as we’d arrived hours before we’d expected, thanks I suspect to some dodgy “shortcuts” we’d taken along tracks that didn’t look as though they were fit for anything apart from yaks or mountain goats to navigate, and while the others slept, I stared anxiously down a vertical drop into deep valleys with foaming and frothing white water below, trying to decide how stable the crumbling edge of the road was likely to be. Why do I inflict these death-trips on myself? Why don’t I take the train like sensible people? But having said that the scenery was stunning, and the prospect of near death tumbling down a cliff into the abyss was at least better than dying a slow and painful death from disease. Right. Anyway, we did arrive intact in Ngawa, none of us happier to arrive than Tsokyi, who’d started to llok green around the gills. We were to stay with her family, of course, and meet up with Yang Yang, Dhopey and Khepey, more girls from Ngawa, whom I’d met in Chengdu, who were relatives of friends in India. They were surprised to see us so early, but quickly had a pot of tea boiling and a table set for lunch. Tsokyi’s mom is renowned for her quick tongue and sense of humour, so we were all soon in fits of laughter. Shortly afterwards, Dorje, Singye and a friend, Jamyang stopped by, as they had heard I’d be arriving that day. Dorje and Singe are friends from the Tharshul school, and they’d been in Ngawa, taking courses at Kirti monastery for the past few weeks.

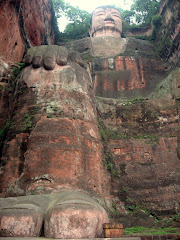

Ngawa is a small town nestled in a long narrow valley, with one long main road, and three or four crossroads. At the eastern edge of town, on the way to Chengdu, was the large Ser Gonpa, a Jonang monastery. I was hoping to meet up with an old friend, Tashi Choekoe and his brother Choemphel there the next day. On the other side of town was Kirti monastery, housing about 700 monks, which had suffered terribly during the uprising in 2008. I asked around for Tashi Choekoe’s phone number, not difficult to do, as everyone knows everyone, and monks returned from India are fairly well known. Yes, no problem, Choekoe was there, and was now the abbot! That made me a bit nervous to go see him, I hadn’t realized he’d become an abbot. Protocol here is a bit more difficult in some ways than India, but I knew he’d be upset if he found out I’d been in town and hadn’t gone to see him, so we arranged to go at noon the next day. Meanwhile, yang Yang and Dhopey hauled Tsokyi and I off to Yang Yang’s family’s teahouse, where we sat chatting over hot tea and dinner, before going out to a dance hall to watch a performance of dance and song by a troupe from Dege area. There was a huge audience of nomads, and the usual hooting, cheering and hollering of appreciation at the end of each number. It was almost as much fun to watch the audience as the dancers, and they seemed to spend about as much time watching me! I was the first foreigner in town since at least March 2008, as the area had been closed, and since it was bloody freezing, and there were no buses, there weren’t likely to be hordes of tourists rushing to come anytime soon. Around midnight Tsokyi and I were struggling to keep our eyes open, so we all left, running up the street arm in arm to keep warm, laughing and singing. Not long afterwards, I was curled up under a huge pile of quilts and blankets, so heavy I could barely move, but toasty warm. It seemed mere seconds had passed before I opened my eyes again and found it was already morning. We got up, had a quick wash in icy water at the pump, and dashed indoors for breakfast of coffee and tsampa porridge. The plan for the morning was to visit Kirti monastery, a big Gelukpa monastery built in the 15th century, so after breakfast we set off through town. It was odd to be there, after hearing so much about what had happened there the past year. You could still see bullet holes in the shop windows. One of the problems with speaking the language was that I spent the next weeks of travel listening to all the stories of what had happened that year, all the people killed, arrested or missing. It was good to know, in a way, but oh so very hard. Sitting listening, hearing terrible stories, and ending up with all of us in tears was how I spent many an evening over the next weeks. A lot of that I can’t write here, but I will never forget what I heard. We arrived in the monastery, and made a detour off to the left to see the huge Buddha statue outside the monastery wall near the Snag-khang, where juniper was burnt as incense. Stopped to chat with some extremely cute and extremely grubby young novice monks, who wanted their photos taken. They were thrilled by the digital camera, where they could see their own photos, and it took a while to peel ourselves loose from the admiring crowd and meet up with Yang Yang and Dhopey who were waiting to meet us at the base of the chorten. Together we wandered into the monastery proper, to watch the debate sessions and the young monks training for the Monlam Cham dances. The air was crisp and cool, but warmed by the late morning sun, and the monastery buildings beautiful against the hills and the vibrant blue of the sky. The monks robes were deep maroon, as they swooped and spun in the intricate steps of the Cham dances, while the shouts and handclaps of the debate, and the scent of juniper made me homesick for Gomang. It was all very idyllic and beautiful, until you looked closer and noticed the military outposts with their machine guns on the hills overlooking the monastery, and all the video cameras fastened to the electricity poles. Only then did you realize that it was all an illusion of peace and happiness. We left shortly afterwards, planning to head back to Ser Gonpa to meet Tashi Choekoe. A friend’s brother had arranged for his brother to meet us, and he drove us down through town out to the monastery. We were shown to the abbot’s house, and I went inside, kadag in hand, looking forward to meeting an old friend. Was shown into the room, to find that it wasn’t Tashi Choekoe at all, but another monk, also called Choekoe, who had also been in Gomang! I pretended, quite successfully, I think, that it was him I had been intending to meet all the time, and we chatted for a while about news from back “home”. He gave me Tashi Choekoe’s phone number, and it turned out that we had probably passed each other on the road the day before, as he had gone to Chengdu with his brother the previous morning! Afterwards, we strolled around the monastery for a while, admiring the yellow and gold chorten before heading back into town to shop for new music cd’s and have dinner. That night, I stayed with Yang Yang’s family…it was a bit like musical beds in Ngawa, as I was invited to a different home each night! The next day we were to go out to Ngawa Gomang monastery, something I was particularly looking forward to, since it was the home of many friends, and I’d heard so much about it over the years. Ngawa Gomang is about a 30 minute ride out of town, through some small villages, in one of which Dhopey lived. We were to stay with her a couple days later. The monastery also housed about 700 monks, and sprawled across a large area of land. There was a beautiful chorten at one end, and after doing kora around the main prayer hall, and checking out the debate ground, we headed in that direction. To get there, we had to pass the monastery school buildings, also closed down this year. Once at the chorten, the monk attendant was more than happy to let us go to the top levels, and into the shrines. At the top, the chorten was covered in gold leaf, and painted with the huge Buddha eyes facing the four directions, like the famous stupas in Nepal. From the top, we could see out across the monastery and the valley, as far as the snow-laced mountains in the distance.

After chatting with the monks for some time, and taking loads of photos to send back to friends in Gomang, we headed back down, as it was nearly time for debate to finish, and we wanted to meet up with some monks who were relatives and friends to friends of mine back in Gomang. Stayed with them, exchanging news and gossip, and drinking endless cups of tea before returning to town, promising to come back the next night for the Parchen Damcha ceremony. The plan for the next day was to meet up with Dorje, Singye and Jamyang, and go for a trip up into the hills overlooking town, so we could get a panoramic view of the whole valley. This was arranged for early afternoon, and after a leisurely morning, and a visit to family of another friend, we met up in Kirti, and drove up into the hills. Standing on the edge of the hilltop, we could see the whole town below, and count as many as 9 small monasteries dotting the hillsides around the town. Ngawa is full of small monasteries, Kirti, Ser Gonpa and Ngawa Gomang are probably the largest of them all, but there are many smaller ones, ranging in size from 20 to a couple hundred monks, and from several of the different sects, Gelugpa, of course, but also Nyingma, Jonang and Bon. We stayed there gazing around and taking photos until we realized how badly we were shivering in the gusting wind, then headed back down to spend a couple hours chatting in a teashop. Dorje and the others were trying hard to talk me into changing my travel plans, as I’d originally planned to go to Machu, then Lichu, and they tried to convince me to go to Dzoige instead, as they wanted me to stay with their families. Didn’t take much persuading, as I’d been to neither place before, and wasn’t too bothered which direction I took to Lichu. So Dzoige it became, and they spend the next hour calling friends and families, telling them I’d be coming. This trip is turning out to be a bit like being a parcel, shipped from place to place, from friend to friend! The next day, Tsokyi and I planned to head back out to Ngawa Gomang, but first, we were to stop for lunch at the home of another Gomang friend of mine. He’d not seen his family for about 12 years, and I was under orders to take lots of pictures. We were picked up by one of his brothers, and drove off up the road to the monastery, but turning off at one of the villages to the family’s home. Tibetan houses in Ngawa are very different from those in the Kham or Gyalrong areas. Here they are 3 storey farmhouses, but of large bricks made of back clay mixed with grass, and plastered over with more clay, then surrounded by high walls in the same method, creating impregnable fortresses, guarded by huge furry black and tan Tibetan mastiffs the size of small ponies! Once inside the walls, the houses look tall, wider at the bottoms than at the top, and splashed with whitewash and ochre. The first floor is used for livestock and a storehouse for their feed and tack for the horses. The second and third floors are reached not be stairs, but by logs carved with notches, worn smooth with years of use. These are not so easy to climb, though the Tibetans ran up and down with the ease of a lifetime’s practice. I was much less confident, contemplating with horror the prospect of having to climb down at night if I needed to go outside for a toilet break! This is never an easy mission at the best of times, as one has to negotiate the way past the family guard dogs without getting eaten or mauled, and it’s always pitch black, as there’s no such thing as streetlights here! Nights in Tibet are stunningly beautiful, with more stars than I’ve ever seen anywhere else, even at sea, the sky a velvety black, and the wind cold and clean. But I digress…

The second floor was used as storage, and had prayer wheels around the walls, that we spun before climbing up to the next layer where the family really lived. Here was the kitchen and the warmth of the stove, lots of good smells, as they’d obviously been preparing a feast for us. I was introduced to my friend’s parents and the rest of the clan, brothers, sisters and their spouses, and innumerable children with ruddy cheeks and runny noses. After gorging ourselves on platters of meat and momos, and exchanging news, the photo shoot started, with everyone wanting to have their photo taken with everyone else. The more the merrier, I figured, as I’d send them all back. After that, we went outside to take some more in front of the house, then drove out to another village, to meet the family of another friend, in which all the above were repeated in pretty much the same order, except that it was difficult to eat as much as they wanted me to after one feast was still trying to settle itself in my stomach! Then on to the monastery, to meet up with the monks before, surprise, surprise, another feast. It’s only humanly possible to eat a certain amount of momos in one day, I’d always thought, but it never ceases to astound me how far those boundaries can be stretched if need be. One may not be able to actually walk well for hours afterwards, but at least one can eat enough to satisfy one’s hosts! We hung out with them until they headed off to attend the prayers before the Parchen Damcha ceremony. Tsokyi and I waited a while, then wandered off towards the Tsokchen courtyard, where the ceremony was to be held, and joined the crowds of pilgrims that were shoving their way into the front section of the courtyard, to watch the procession of the main students of the class, decked out in the full regalia and the debate displays later on. We were all sitting on the stone steps leading into the courtyard, and boy was it cold! I was thankful that I was wearing my wooly sheepskin lined chuba, as the bits inside it were warm, it was my feet and ears that were threatening to drop off from frostbite! Poor Tsokyi on the other hand was freezing, as she was just wearing regular clothes and a coat. Still we stayed long enough to watch most of the ceremony, which was to last until the moon rose high enough to show over the top of the courtyard wall. We left shortly before that, as we were to go back with Dhopey and her family, to stay at their place for the night. We left our cameras with the monks so they could take more photos for the guys back in Gomang, and drove off in the dark with Dhopey’s family. She lived in another village nearby, in another of the 3 storey farmhouses, with more of those wretched stairs!

Arrived back to find her mother had kept dinner waiting, the fourth feast of the day! Sat around drinking tea and chatting for a while, then curled up under piles of blankets to sleep. Her mother slept in the next room, in what looked like a big wooden box full of sheepskins in the corner beneath a small altar. There were ropes of drying meat on the walls, and a big wooden churn in the corner. The window was small, with faded patterns traced on the wall above it in reddish ochre dye. The door in the opposite wall opened onto a platform and the log-ladder down to the second storey with its prayers wheels. Burning juniper incense wafted up through the door, creating a sweet-smelling haze in the room. I’d have liked to take some photos, or better yet, paint it, but we’d given our cameras to the monks, and anyway, I wasn’t sure it would be terribly polite. The next morning, we had to go back to the monastery to fetch our cameras, and we decided to go on horseback. Dhopey’s family owned two horses but only one saddle, so she and Tsokyi

Doubled bareback on one, and I got the other one with the saddle. We trotted off through the village, and I figured out why Dhopey had loaded her pockets with small stones before we left: to stop the dogs from chasing us as we passed the other homesteads. It was about a half an hour ride, and we rode leisurely along, talking and laughing until we reached the monastery. We brought the horses right into the monk’s enclosure, and tied them where they could nibble at a pile of hay in a corner. Didn’t take long to get the cameras back, and after a quick cup of tea, we headed back to Dhopey’s place, as we were to be picked up and brought back to town at noon. Back at Tsokyi’s home, I decided a hot shower would be a priority, as there’d be little likelihood of another for several weeks, and I was feeling fairly grubby. Upon my return, I found that Tsokyi’s mom had had a Ngawa style chuba made for me, slightly different from the Tso Ngon one that I was wearing. I’m starting to be able to pick out where people are from by the difference in their clothes now, even the more subtle differences. Does that mean I’m getting closer to being a native?! I was to leave the next morning, which would entail getting up at the unearthly hour of 5am, when all sensible people, especially those living in a place where noon is cold, let alone predawn, which is absolutely freezing, should still be tucked up warmly in bed. However, the alarm went off at 4:45, and up we got (a miraculous endeavour for Tsokyi, who can sleep until noon if left to her own devices!). Down to the bus station, and on to the Dzoige bus, still half asleep despite the cold. It had been quite an intense 5 days, so much had happened, and I’d heard so much, and met so many people. Hadn’t really all sunk in yet, and wouldn’t have a chance to, as most of the next stops of the trip were equally intense. Writing this after having returned to Santai is like reliving the whole trip, good and bad.

Dzoige (Ruor’gai)

Most of the trip to Dzoige was in the dark, and grey light of dawn, so I didn’t see much of the passing countryside. I was met at station by Konchok, a friend of Dorje and Singye, from their monastery. I had spoken with him several times, as he’d gotten my number from Dorje after I returned from Tharshul this past summer. He sent messages now and then to improve his English, and keeps saying he wants to come live in Santai for a month or so to learn English. I was shocked to see that he was on crutches, and appeared to have only one leg, but didn’t want to be rude by asking why. He swung along on them as though he’d been doing it all his life though, and I found out later from a friend that he had. He’d been injured badly when he was about 8, in a horse race where the horse ran away out of control, and was hit by a car. He was lovely to hang out with, with a permanent grin on his face. We arranged to stay the night in the station hotel, as it was close and convenient to drop off my pack and to leave the next morning. Dzoige is a strange sort of town, full of Tibetans, but built in the new and ugly version of communist cinder block square buildings. Still, it was bustling with activity, with a large market in one street, with Muslims selling large frozen chunks of various dead animals, mostly yak and sheep, and carts with fruit or vegetables, both fresh and dried. Loud Tibetan music blared out of the shops selling CD’s and cassettes (yes, they still sell and use cassettes here!) We had a quick break for lunch, stopping at a small restaurant that sold some of the best momos I’ve ever eaten, before heading to the outskirts of town to visit the 18th century Taktsha monastery, which houses about 100 monks. Konchok told me I simply had to visit the monastery’s library, which had been built just a few years before. It was a beautiful new 3 storey building, painted ochre yellow. The first floor, Konchok told me, was the library, while the second floor had been made into a museum, and the top floor was a small temple. It had already become renowned in the area for it’s collection of books, mostly in Tibetan with topics ranging from Buddhism texts and history to mythology, medicine and astrology. There are also books in Chinese and English, but the monk who had sponsored the project was focusing on the old texts, trying to build up a comprehensive collection. However, we had no luck finding the gatekeeper, and the doors to the compound were locked. Instead, we did a couple of kora, and wandered around the monastery buildings, going into the main prayer hall and several temples. Dzoige doesn’t tend to be on the tourist circuit, what there is of it, at least not for foreigners, and people looked at me as though I’d dropped from the moon, though they were thrilled when they discovered they could talk with me and I could understand most of what they said. Finally, we found a helpful monk who said that if we came back the next morning, he’d arrange to let us in, even if the gatekeeper were away again. So back into town, and we went next to visit some of Konchok’s family in the local school. The kids had just finished writing an exam, so were milling around outside, but crowded round to listen when we stopped to talk with Konchok’s niece and nephews. Next stop was to visit more of his relatives, who had been forwarned of our arrival, and prepared a huge meal, yet more slabs of boiled meat and momos! Spent the evening there, listening to folk tales from his old uncle, who sat near the fire, arthritic hands with their swollen joints beautiful in the firelight, as he spun his rosary beads while holding his audience captive by his tales. So many of these old stories are being lost now, as TV and radio take the place of the evening story telling sessions, there aren’t so many people left now who know all the old legends and fables. Back to the hotel, and up again early in the morning for a quick breakfast before heading back to the monastery to visit the library. True to his word, the monk was waiting outside to let us in, and we wandered through the library, admiring the rows of books in their brocade and cloth wrappings. Next upstairs to the museum level, with its big glass cases full of all sorts of antique items: suits of chain mail, and weaponry, household items like churns and all kids of other utensils, which looked to me like instruments of torture, but Knochok assured me were cooking tools of various kinds. There were old leather prayer wheels, and faded robes and other monk regalia, as well as a whole set of cases containing ancient texts printed and illustrated with gold and silver. Many of these would have been hidden away to survive the cultural revolution, and brought out not long ago, to be stored in museums. In the centre of the room was a big glass case holding a Kalachakra sand mandala. It was fascinating, and I could have spent much longer looking at all the curiosities. There were even things like a sheep skull with three horns! Finally upstairs once more to the temple, with its gold covered status of Tsongkapa and Dolma, and the grand views out over the monastery and town below. By the time we finally left, it was early afternoon, so after a fast lunch of thukpa (noodle soup), we grabbed our stuff from the hotel instead of the bus, as we’d originally planned, were picked up by one of Dorje’s friends’ brothers, who had a car, and had been told to play chauffeur for us! We left town, heading north on the road towards Lichu, but turned off after about half an hour, onto narrow dirt track that looked like a cattle path, and didn’t seem to lead anywhere except randomly onto the grassland in the direction of the foothills. However, after bumping and bouncing along for another half hour, a village came into sight, and we turned off the track, and drove straight across the grassland towards a cluster of houses on the eastern side of town. We were going to visit Singye’s family first, I was informed, then had several other families to go and see before going up to the monastery. We turned into the family’s courtyard, but had to sit and wait in the car while the family pulled off the huge mastiffs, which were leaping at the car, and barking madly, and appeared quite willing attempt to bite holes through the steel to get at us! I’m not afraid of dogs, but these beasts are more like a cross between a wolf and a grizzly bear! They were eventually dragged off, still barking, and we went into the house to find, surprise, surprise….a feast of meat, momos and fried bread laid out on the table near the stove. Konchok and I sat down as guests of honour, and the family crowded round, thrilled to have a foreign guest. I suspect that I was probably the first westerner to visit their village, as any other foreigner would have no reason to stop even if they had made it out to Dzoige. After an hour of talk and eating, we all went outside, (the dogs had been chained, though they were leaping against the restraints, growling and barking) to take photos, as Singye had asked. Next stop in the list of places to visit was Konchok’s mom’s place. She was living with one of his older sisters to help look after the kids while the sister and her husband were out working in the fields or in the hills with the yaks. There too, a feast had been laid. Fortunately, forewarned of how many places we were to visit, and knowing by experience that there was going to have to be an awful lot of eating that day, I’d carefully not eaten much at the first place. There is a knack to this, it’s not as easy as it sounds to not eat much, but appear to eat enough to make the hosts happy that you have enjoyed their food. I can’t count the times I’ve come away with my pockets or bag full of chunks of meat or bread that I’ve carefully pretended to eat! That’s one good thing about the Tibetan chubas, they have long sleeves and the front pouch into which it’s really easy to slip hunks of meat when noone is looking, to either eat later, or feed to a dog! Next stop was Dorje’s family, with, yes, more food, and a roomful of people. I was impressed at how big the family was at first, until I found out it was actually the family and several neighbour families, who’d come to see the strange foreigner who had appeared in their midst. We had a grand discussion over where Canada was in relation to Tibet, and they were bemused by the idea that when we were getting up in the mornings, my family would be going to bed. This necessitated a whole series of drawings of the earth and the moon as well as a map of the world. Most of these people had never been out of their district, especially the women. A few of the men had been as far as places like Xining or Chengdu, and one or two had been to Lhasa on pilgrimage, but that was the extent of their travel. After a couple hours there, we carried on up into the village to Konchok’s home, where his father and several brothers lived with their wives and children. We unloaded our stuff here, as we would be spending the night there, and instead of the feast (which would come later) had a quick cup of tea with the driver before heading up to the monastery. It was called Dzoige Sera monastery, a branch, I assume of the large Lhasa Sera. There were about 100 monks, I was told. Though we didn’t see many, there was smoke rising from many stovepipes on the monks’ quarters. Konchok got the keys to the prayer hall and temples, and we did kora as well as visit each of the main buildings. We went into the protector deity chapel as well, and I was impressed by the paintings on the walls, some of which I’d never seen before. It was dim inside, and there were bodies of stuffed animals hanging from the ceiling. The door curtain had a huge white ceremonial skull appliquéd onto the rough woven yak hair cloth. The chapel was perched on the hillside overlooking the monastery, with great views of the valley below. After wandering around for a while, the driver began to look impatient to head home for his dinner, so we piled back in the car after yet another photo shoot with friends, and went back to Konchok’s family home for dinner ourselves. His sister was waiting to prepare the meal until we arrived, so while we talked and laughed (his father was a tiny little man, with a toothless grin and face full of laughter wrinkles, and had a great sense of humour), I helped his sister in laws make the small momos for mo-thuk (momos in soup). This is one of my favourite meals, and that night’s was no exception, delicious savoury bites of momo in a steaming broth. Before we had begun to prepare the meal, I’d gone out to enjoy the view over the village. Dusk was falling, and smoke from the cooking fires created a mysterious haze over the village houses. In this area, unlike the stone walls of Lhagong, or the high baked clay fortresses of Ngawa, the enclosures were protected by walls made of 6 or 7 foot high poles bound together to form a formidable topped with whittled spikes, and plastered about halfway op with yak dung and clay. In the half light, it was beautiful and serene, except for the barking of dogs and the lowing of the yaks and bleating of sheep as they were herded back into the village for the night. The whole clan gathered for the dinner, and it was fun to sit and watch the interaction between the different generations. There were 4 generations in the one room, with Konchok’s father as the patriarch, his big sons, ruddy cheeked and strong looking, their wives, with their strong arms and workworn hands, and their children, the oldest son’s daughter was also there to visit, with her very new baby, who looked to be not more than a few weeks old. The daughter herself was only 16, and been married for just a year. In many of the small village and nomad communities, people still marry very young, boys are usually around 18 -20, and girls as young as 15. Unless they go to school, and more and more do these days, it is embarrassing for a girl to still be unmarried by 18. It was a great evening, enlivened by peals of laughter at Konchok’s dad’s jokes, and later in the evening, by songs and story telling. It was warm and comfortable inside, while the wind blew and the dogs howled outside, and when the beds were made up, I was asleep within minutes.

Lichu (Luqu)

We were all up in the wee hours of the morning, to ride out to the roadside so I could catch the 6am bus to Lichu ( which means “River of the Dragon God). It was still dark outside when the family gathered to say goodbye, and for two of Konchok’s brothers to arrive on their motorbikes, ready to ride the kilometre down the dirt track to the road. Konchok clambered on behind one brother, and I behind the other, wearing my pack, and leaning forward as much as possible to balance its weight. Much to my horror, Konchok and were both given thick clubs to beat off the dogs if they were to chase us, biting at our legs! As we sped off into the darkness, I anxiously scanned the passing gates on the watch for the huge Tibetan mastiffs that slept nearby on guard. Fortunately, they all seemed to be content to let us pass, though I saw more than one huge head raised to watch us. About 20 minutes later, we reached the road, and the two men parked the bikes on the grassy slope nearby, as we stood shivering in the dawn, huddling with our backs to the icy blasts of the wind blowing down off the hills. Finally, we could see headlights, but on the grassland, distance is misleading, and it took ages for the lights to get near enough for us to tell that it was the Lichu bus. The men flagged it down, and I was bundled onto the bus, my pack stowed in the luggage compartment below, and off I went, waving through the window at my friendly hosts. As we rounded the bend, I could see them still standing and waving in the pale morning light, despite the fact that they must have been freezing, and wanting to get back for breakfast. I was a great curiosity to the Tibetans on the bus, as this was not a route commonly travelled by foreigners, and especially not the past year. Also, I had boarded at a remote village, and they had heard me speaking Tibetan. All enough to make me the main topic of conversation, and as usual, I ended up answering the usual questions, where I was from, why I could speak Tibetan, was I travelling alone? Was I married? Where were my family? It was enough to entertain them for hours, as those nearest me asked the questions, and passed the answers back through the bus to the other passengers. In this way, the trip passed quickly, and I didn’t get much chance to look out the window until we reached the turnoff for Lhamo (Langmusi in Chinese), and the bus stopped to pick up several more passengers on the roadside. Much to my astonishment, I saw that I recognized one of them, Samdup Sangye had decided to meet me on the way, and stay with me in Lichu. So we sat and chatted for the final hour and a half of the trip, and then got off the bus at the little station in Lichu, in search of a hotel for the night, as another friend, Samdup was planning to join us later that afternoon.

Lichu is a small nomad town, quite new-looking, and named after the river that flows alongside the town. We wandered down the main (and only) street, until we found a brand new hotel, strung with prayer flags, and with a load of monks outside. Apparently it was the official opening of the place, which had just been bought and renovated by a local monastery, and they weren’t actually open for business until the next day. However, Samdup Sangye begged and pleaded, and when they saw I was a foreigner, they decided it was a good omen that their first guest was to be from so far away, and they decided to allow us to stay. When we asked the cost, we were told we could pay whatever we liked, they hadn’t set the rates yet! Once in the room, the monks brought in plates of fruit and biscuits, and invited us down the hall for tea. This turned out to be a feast, with them serving us bowls of thukpa, and sweet rice with juoma, as well as huge platters of meat, fruit and sweets. We tried to refuse, but it was all part of the inauguration ceremonies, and we were obliged to accept out of politeness. I wasn’t too unhappy about this, as I’d not had time for breakfast before leaving so early that morning! After that, we went for a walk round town, posing for photos in the main square and by the river. Lichu is one of the main Tibetan rivers, along with Machu, Drichu, Sanchu and others. It had snowed in the night, and a cold wind was blowing, so we didn’t stay out long, but went in search of a cyber café. Samdup Sangye had recently learned to use email, and I wanted to check mine as well. While we were there, we got a phone call from Samdup who had just arrived in town. He came up to join us, and I taught him to use email as well. Later in the evening we found a Muslim restaurant for hot noodles and tea, before heading back to the hotel to play cards and watch kickboxing finals on TV, amusing ourselves by predicting the winners before each match, and deciding it was a really stupid sport! That night, Samdup Sangye and Samdup decided they would go with me the next day to Tsoe to see the 9-storey Milarepa Lhakhang, and from there to Labrang to meet up with the other students before returning to Lichu. So it turned out I’d have travelling companions for the next couple days!

Tsoe (Hezuo)

So we set of mid morning the next day for Tsoe, about a 2 hour trip by bus. I enjoy the bus rides for the most part, because the landscape is stunning, but the drawback is that all the buses seem full of chain-smokers determined to get through as many packs as they can in the shortest possible time. Wrapping my scarf around my face to cut off the worst of the fumes, I gazed out the window. The bus was crowded, so Samdup Sangye, Samdup and I were sitting separately, and I saw after about 20 minutes that they had both dozed off. We drove through deep valleys, alongside rivers frozen several feet in along each bank, but still running cold clear water so deep it looked black against the ridges of ice.

We arrived on the outskirts of Tsoe, and I was surprised at how large the town was, and how Chinese. It was lower in altitude than most other large towns in the area, and the Han Chinese had obviously preferred to settle there. We got out at a large bustling station on the edge of town, and I was quite glad that Samdup was with us, as he knew the area, and where to go. We piled into a taxi, and sped off for the centre of town, until we arrived in an area full of Tibetan shops and restaurants. We stopped in front of a biggish hotel, and Samdup informed us that it was the best place to stay. That was great except that when we went in to register, we were told that foreigners weren’t allowed to stay. We got the same answer at several other hotels we tried, much to Samdup and Samdup Sangye’s amazement and my disgust. I never could work out the point in that restriction, oughtn’t they to be glad to accept our money? At any rate, we ended up walking for nearly an hour around the area in search of a hotel that would 1. accept foreigners 2. accept monks and 3. meet Samdup’s standards of comfort and cleanliness. This third was possibly the most difficult of the three as he was determined to find a place that was clean enough for me to stay in, and none of my protests that as long as there was a fairly clean bed I’d be happy would change his mind. Bless him. After about an hour, we eventually did find a place that passed the above qualifications, and it was a relief to dump our stuff, and have a rest before looking for a place to eat. None of us spoke great Chinese, so it was a bit of a mission, but we opted for our usual resort of a Muslim restaurant and noodles.

I didn’t like the town very much, it was very Chinese in feel, and very unattractive with the usual soviet style cinder block housing. After lunch we went to the outskirts of town to check out Tsoe monastery, and the famous 9-storey building, the Milarepa Lhakhang.. I’d been wanting to come for ages, and Samdup and Samdup Sangye both laughed when they said they lived only a few hours away, and had been through town countless times, but had never been to the tower themselves. So we had a grand time posing for photos and wandering around the monastery. The design of the tower is pretty unique in the world of Tibetan architecture, and the inside, as with most temples is a mindboggling array of paintings, murals and statures. Apparently there is also a meteorite, though we didn’t see it. Not many monks around, though I’m not sure whether it was because there were few left, or because many of them had gone home for the winter holiday. At any rate, apart from the Lhakhang, there wasn’t much to see, and after an hour or so, we headed back into town. Samdup had some shopping he wanted to do, and Sangye Samdup and I tagged along, chatting, and enjoying the usual double-takes and remarks of passersby as to the sight of a foreigner in Tibetan dress.

Apart from the Milarepa Lhakhang, there wasn’t much to see or do in town, and we decided to leave fairly early the next morning for Labrang, where we were to meet up with more friends, and I had a few errands and people to meet before carrying on to Repgong.

Labrang (Xiahe)

So back on the bus again the next day for the 2 hour bus ride to Labrang. I had never gone via the south before, but always from the north via Jianza and Repgong. From the south, the country we were passing through is called the Bora region, interesting for me, as I’ve several friends back in Gomang from that area, and I amused myself by staring out at the passing villages, and wondering if I was looking at the homes of my friends or their relatives. We drove past Bora monastery, and I decided that next time I was in the area, I’d get off and have a look round. In the meantime, we sped on past sleepy little villages, the women out in the compounds spreading yak dung to dry in the sun, and the huge Tibetan mastiffs sprawling on their sides soaking up the heat from the midday rays.

Around noon, we pulled into the bus station, and it was nice to be back in a primarily Tibetan area, however much it had been built up for tourists after being in the ugly town of Tsoe. This area is one many people visit if they can’t get into the autonomous region of Tibet, and in many ways, it’s more Tibetan here than in Lhasa these days. After Lhasa, this is one of the main pilgrimage sites, and on the streets you can usually see a mixture of local nomads and shopkeepers, monks and pilgrims from all over Tibet. We were met at the station by Gedun Samdup, another Tharshul student, and “Tashi”, a friend of mine. Didn’t have to go far this time to find a hotel to stay in, and we booked a room with three beds, as more friends would be joining us later on. (In previous hotels, we’d gotten doubles, as Samdup Sangye and Samdup shared a bed to save cost. Most Tibetans seem to do this, and the hotels don’t seem to mind more people staying in a two or three bed room). Not long after we arrived, friends turned up: Chezin, Longtok and Sangye joined Gedun Samdup, and we all sat round on the beds catching up on news and telling jokes. Main topic of conversation of course, is whether the Tharshul school will be permitted to reopen, with everyone hoping it will. After lunch (more noodles) we wandered off down the road, window-shopping and chatting. We’d gone into one market, with stalls selling “authentic” Tibetan jewelry and trinkets for tourists, and were checking out a book stall in a corner, when I heard someone call my name. I looked up expecting to see one of the students, but it turned out to be an old friend from Gomang! He was from Serta, and had come to Labrang with a few friends to take some classes. He was as surprised to see me as I was to see him, though he had heard I was in Tibet, he’d obviously not expected to meet me randomly in a shop in Labrang. We chatted for a bit, exchanged phone numbers and arranged to meet for dinner the next day. Back to the hotel with the monks, stopping to pick up some instant coffee drinks and biscuits on the way, where we spent the night sitting round talking and laughing. The next morning though, Samdup wasn’t feeling well. He’d had a cold for a few days, and couldn’t seem to shake it, so he stayed in bed after an IV glucose injection. I’d caught a cold as well, but figured it’d pass, so I set off that morning to meet the friends I needed to see and do some errands. This turned out to be not as easy as I’d expected for various reasons, though I did manage to find my friends, and we went out for lunch together. I turned out I’d need to stay for at least two more days to finish what I needed to do. Walked back through town in time to meet my Serta friend for dinner. He was with a group of friends, and we sat and talked over a hotpot dinner. More truthfully, they talked, and I listened, trying to memorise everything they said. Back to the hotel for an early night. The next hotel Samdup was feeling lots better, but I was not, so it was my turn for an injection. I don’t tend to hold much with all these injections and IV’s that they give you here at the drop of a hat, but after a few hours, I did feel a lot better. Well enough to go out and finish the next part of my errand. Later in the afternoon, met up with the students near Labrang’s famous gold chorten for another round of photos, and to meet up with another old friend, Thupten Nyima, who’s living just outside the monastery and taking classes. The next day was to be my last day in Labrang, so worked hard to finish all the stuff I needed to do, and met up for dinner with all the students, a hotpot feast which was great fun, lots of laughing and talking, and farewells, as I was to leave for Repgong the next morning, and we’d not meet again until the summer. I was sad to leave, especially Samdup and Samdup Sangye, who had been great travelling companions over the past few days.

This has been a difficult section to write, as there is so much more I want to write but can’t. However, I have all the notes and won’t forget. After the events of the past year, Labrang wasn’t a particularly happy place, the whole tone and feeling of the town was one of fear and suspicion. Very sad, especially for the monks, who live in a state of fear, knowing they are watched. There are cameras everywhere. Enough said.

The next morning, I set off early, with Samdup and Samdup Sangye to catch a bus, but even before we reached the station, a taxi driver beckoned us from the side of the street, saying he had to go to Repgong and would charge me the same amount as the bus. This seemed a good idea, so my pack was loaded in the boot, the driver set off, Samdup and Samdup Sangye waving goodbye from the sidewalk. Not far along, the driver stopped again, hoping to pick up another passenger or two, but there were no takers, so he sped on again, If I’d been a nervous sort, it might have been a wee bit scary, driving off in the semi dark as the sole passenger, through dark gorges and miles of empty grassland. The driver was uncommunicative, his Tibetan wasn’t very good, so we didn’t talk much. However, about an hour later, he stopped to pick up two old nomad men flagging him down on the roadside, and they livened up the atmosphere considerably, talking and laughing until we arrived in the town of Repgong at around 9am.

Repgong (Tongren)

The car stopped to let us out opposite the bus station at the edge of town, where I was met by Gedun Lekshey, who was in town for a few days before heading out back to hi family’s place for the winter holiday. We took a taxi back into town, and booked me into the same small hotel where I had stayed on my last village, up and alley near Rong monastery. During lunch, however, I got a phone call from Lobsang Dargye who was on his way into town from his monastery nearby, and told me not to book a hotel, but to come and stay in the monastery that night, to meet Tenzin and Rapgye and some of their other friends. So we went back to cancel the hotel, and waited to meet Lobsang Dargye. He arrived shortly afterwards, and after doing a bit of shopping for fruit and vegetables in the market, we took a taxi back to the monastery, driving out of town up a dusty road into the countryside, through a few villages, until we could see the monastery, buildings stark white against the hillside, the gold roof of the temple gleaming in the sunlight. There were the remains of an old chorten at the entrance to the monastery, the top destroyed or disintegrated into a heap of stones, covered with grass, but the mani wheels still intact around its base. There were about 20 old women, rosaries dangling from their left hands as they did kora, and loads of kids running around laughing. We stopped just past the chorten, and were invited into a monk’s home. He turned out to be the monastery doctor, and was looking forward to actually talking with a foreigner. Many tourist come through Repgong, and visit the monasteries, but this one was mall and out of the way, with no particular attractions to mark it as out of the ordinary compared with all the bigger monasteries in and around Repgong, renowned for their amazing artwork. He was really interested in my travels, and asked questions about many countries. Several cups of tea, and a photo shoot later, we walked up the hill to Lobsang Dargye’s house, where Tenzin had been preparing lunch. More friends turned up shortly afterwards, and it turned out that Lobsang Dargye and Rapgye had been giving English lessons! It’s always great when your students become teachers themselves! One because it’s great for their confidence, and keep them in practice, two because they’re helping people who would otherwise not have a chance to study, and third because it keeps them learning to stay ahead of their students! After lunch, we went for a walk down to see the old chorten and take some more photos, meeting up with Rapgye on the way. He’d known I was coming, but when he saw us walking he didn’t recognize me because I was wearing the thick chuba and head scarf against the cold wind. Once he realized who I was, he came running up the hill, laughing, saying that I looked like an old nomad women! Monks have such a way with words… bless them! Next stop was the monastery’s new temple, a beautifully proportioned building, bedecked with fluttering yellow cloth, that billowed in the wind. Rapgye galloped off again to get the keys, and came back with the gatekeeper himself, who also wanted to meet the “Injee”. So the crowd of us entered the temple, dark at first, after the bright sunlight outside, but after my eyes adjusted, I gazed up in wonder at a huge new statue of Jampa, covered in gold leaf, but with one of the most serene and peaceful faces I have ever seen. The walls and ceiling of the temple were covered in intricate and colourful paintings. The artists of Repgong aren’t famous for nothing. I have been in many, many temple and seen thousands of paintings and statues, but this one still impressed me. Though a jewel of a place, it’s not on any tourist map, and perhaps it’s better that way. Back to Lobsang Dargye’s place for dinner, and another night of conversation. There were four or five monks apart from Lobsang Dargye, Tenzin and Rapgye, all of whom were eager for a chance to practice what English they knew. After hours of talking, laughing and joke-telling, it was time for bed, and as always, I was asleep just minutes after burying myself under the heavy pile of blankets. The next morning, we were invited for breakfast at Rapgye’s brother’s home in the village, where we sipped steaming cups of milky tea and ate homemade fried bread twists, still warm and steaming. Afterwards, back into the car, and back to town for a quick meeting with Gedun Lekshey before I caught a car to Tsekog, a 2 hour drive south west of Repgong, near the Henan area, settled years ago by Mongolian nomads.

Tsekog monastery

We sped across the grassland, held up now and then by herds of yak or sheep crossing the roads, which all Tibetan drivers take in their stride, slowing down just enough to shove their way through the herds, horn blaring as the animals shoulder each other to the sides. You can look out the window and see the white of their eyes, shaggy coats rough and thick for the winter, breath flaring white in the icy air. The farther we got from Repgong valley, the more wild and remote the landscape became, with vast rolling grasslands rising into undulating hills and snow-clad peaks in the distance. I had rolled down the window a ways to combat the inevitable cigarette smoke, but was forced to roll it up until barely a crack was open because of the freezing cold wind. The town of Tsekog appears like an oasis on the grassland, built seemingly in the middle of absolutely nowhere. Most Tibetan towns are built in sheltered valleys, backing onto hills, but Tsekog sits in the middle of a huge open plain, and the icy winds whistle through town with gale force strength, with nothing to stop or divert them apart from a few mere man-made buildings.