Thursday, August 28, 2008

quandaries and dilemmas...

well, I ended up resolving my dilemma, leaving it until the last minute before making my decision. I've decided to stay another year at Santai. Just picked up my new visa, which is good until August 19. The main reason for deciding to stay is that with the current visa situation in China, at least for the Tibetan areas, I'm not sure I could get back in to the places I want to be if I go to Thailand instead of working here. However, I'm taking a couple weeks off in October (Have already told the agency) and will go to Thailand to visit friends then. I sus[ect I'll be needing a break from Chinese schoolkids by then, bless 'em! Anyway. Figure I might as well save up a bit this year, and see what I can work out about getting u to teach in Qinghai next year. Alot will depend on how the situation evolves. I'm in Chengdu now, just bought myself some paints to keep myself amused for the next few months. Returning to Santai today, and am supposed to start classes as of Monday. So that's the latest newsflash...when I get back, I'll add Marco's message for the girls...

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Summer in Amdo June-August 2008

North to Xining and on to Tharshul

I ought to have learned my lesson after the last trip to keep a proper journal while away, but sense and logic have never been among my better qualities, as all of you who know me well can confirm. So here I sit yet again, trying to write an entire summer’s worth of stories into a few paragraphs that won’t take absolute days for you all to read.

The last day of my contract was May 30. I had classes in the morning, and had packed all my stuff ready to go, so that I came back to my flat, dumped my books, picked up my pack and was off. The other teachers and students, bless ‘em, still had a good month or so to go and all the exams to take. I was more than happy to leave for various reasons, one of the main ones being to head for the hills and ground that didn’t shake! Spent just a night in Chengdu, and was on the train the next day for Xining. Fairly unexciting train ride, I slept most of the way. It was several hours longer than last time, as we had to detour around the earthquake damage at Mianyang, but finally arrived around mid afternoon, and I got a taxi over to Phuntsok’s. Spent just a night there as well, as I wanted to catch the first bus I could back to Tharshul. A much warmer ride than the one I made at Losar, where my feet had frozen in solid bricks hours before I arrived. It was nice to sit and enjoy the scenery without having to stomp my feet in order to prevent getting frostbite.( This does tend to distract just a wee bit from one’s overall enjoyment of the landscape, I find.) Took the bus via Thrika (Guide) again, though should have asked whether the construction begun last year had been completed. I was in the very last row of seats, and after leaving the highway to Thrika, we drove for about 6 hours on a “road” that seemed to largely consist of potholes and large rocks, which I suppose at some point will be used to make the road smooth, but at that point seemed to serve the sole purpose of bouncing all the passengers in the back half of the bus off the roof. I vowed an hour into the drive never to take that route again without a crash helmet. And the rocks and potholes were the least of our worries a few hours later. The road had been literally washed down the side of the mountain by heavy spring rains, and a temporary track of sorts had been scraped into the side of the cliff, often at a 45 degree angle, so that those of us on the right side of the bus found ourselves staring straight down the cliffside into a valley full of huge boulders and other debris obviously the result of fairly recent landslides. Those on the left side had an only slightly more reassuring view of the scree covered cliff rising high above, dotted with signs warning of avalanche. After a few hours of rattling along uneven roads on the mountainside, inching our way on temporary tracks around bridges that had collapsed and carefully not looking down at rusted wrecks of vehicles at the bottom of valleys, one does seem to become somewhat immune to the terror or imminent death, and the discomfort of being banged and bounced around becomes the more overriding concern. At any rate, we did eventually arrive in one piece, (a slightly bedraggled, shaky piece, but one piece for all that) and the landscape between bounces was stunning. Got into Mangra (Guinan) several hours late, to find all the guys waiting for me. Just like coming home, it was lovely to be taken straight to a restaurant for lunch and a quick wash. Then off to the police station to register my arrival – a lesson learned the hard way from my Losar trip – and everything seemed fine, filled out the usual form, handed over a Xerox of my passport and a photo, then we all piled into a car and headed for the monastery. How green everything was, the fields full of wildflowers, and the nomads’ tents and yaks dotting the hillsides. No smoke or smog, and miles and miles of blue sky, hills and hardly a human in sight.

Pulled up to the monastery school, which had been closed for the holidays during my winter visit, and was shown into the room which had been prepared for my arrival. Nice to have my own space, complete with a bathroom and HOT WATER! That had been the only real drawback last trip, not being able to shower at all apart from 2 or 3 trips to town and the Muslim bathhouse. The students were in class, 60 monks ranging in age from 15 to 30 from all over Amdo (Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan). They were as curious about me as I was to meet them, but there was no time the first day, as I was hurried off for dinner, and spent most of the first evening catching up on the latest news with my friends.

The next day was to be my first day of classes (no rest for the wicked…!). Choezin did sit in on the first day’s classes, to make sure the students could all understand my hybridized version of Amdo dialect. The first class is always hard, especially mid term when you don’t know what they have already learned, or what level they are at. They were all really shy, but that soon wore off after the next few days. I had however, arrived just shortly before the midterm exams, and the students were to have a 20 day summer holiday. Up here, the summer holiday is short, and the winter holiday longer, because of how cold it is in dorms and classrooms that are unheated. So I helped with the exams, then found out that 14 of the students had decided not to go home for the holidays, but to stay and learn English. So we set up a schedule that ended up with them having 4 classes a day, 2 of which were open to other monks from the monastery as well, Rapten, Namgyal and a few others who had studied with me during the Losar holiday. I also had 2 classes a day for Choezin, Shedup, Ngawang, Khenrab and also Padma Reypa (an old, old friend from Gomang, now the abbot of a big Nyingma monastery in Golok) Gedun Lekshey (another old friend from Gomang, from near Repgong), Gyamtso and Thupten Nyima (also Gomang monks, from Thrika). This group are all friends from India, and several of them had travelled up to stay at Tharshul for the summer to study English again. So in total, I ended up teaching 6 classes a day, 2 in the morning, 4 at night, and drawing class all afternoon.

Horrible, Terrible crazy students…..!

The group that stayed for the holidays became really close friends. We cooked together, ate together, went for walks and had picnics, and spent hours laughing together. We all ended up with various nicknames, many with long stories behind them, which are probably only funny if you were there, so I’ll spare you the details on that! We called ourselves the Horrible Terrible crazies…and our group included: Jinpa, from an area near inner Mongolia, Choegyam, Shedup and Konchok from Tseko, Black Konchok, Dorje and Gyamtso from north Sichuan, Longtok, Chedak and Tashi Nyima from Tso Ngonpo (Qinghai Lake), Damchoe from near Labrang, Jinpa from Jianza, Paljor. And Choezin’s nephew Tsegya, who’d studied with me at Losar as well during his school holidays.

We became close friends, aided by the fact that it was Yarney (the monastic season where the monks aren’t permitted to leave the monastery, and no women are allowed in, not even the monks’ mothers. There are various other rules, such as no cutting grass, or walking on grass if it can be avoided. This is to make the monks remember all the lives of bugs and small creatures that are taken by people blindly tramping on the grassland) So although I’d been told I was an exception to the rule, and was allowed in the monastery grounds, I was careful not to abuse the privilege and offend the senior monks, so I stayed in the school compound beside the monastery, and friends came over to see me. That meant I spent all my time with the students in the school, and we worked hard at lessons.

That group worked really hard at their English during those 20 days, and improved more than I’ve ever seen any group of students do in such a short time. They attended 4 classes a day, chatted and joked with me during mealtimes, and when assigned 10 sentences for homework, did 50. I gave them 2 “exams” to judge their progress, and was incredulous at how well they did. We decided to hold an exhibition type competition for the first day of regular classes when all the students returned, and we practiced hard for a week beforehand, inviting Choezin and the other teachers to watch our progress. On the day of the actual competiton, we invited all the teachers, Aku Tashi, the Gomang monks, and anyone else who cared to watch to come and see. I was really proud of them, and they were proud of themselves, almost in awe at how much they’d learned in such a short time. Sungrab turned up, and was really impressed with how much they could understand and talk. The way I set up the competition was to divide them into two teams, fairly well balanced in ability levels, and made a large dice out of cardboard. If they rolled a 1 or 2, they had to define and spell a vocabulary word (they’d memorized 50). If they got a 3 or 4, they had to translate my Tibetan sentence to English, and a 5 or 6 meant they had to translate my English sentence to Tibetan. It was a lot of fun, and we spent as much time laughing as learning during our 20 day “summer school”. I have never had such a good group of students, one that worked so well together and had such a bond of camaraderie.

Even the students returning commented on how they wished they’d not gone home, since they had really missed out on a great summer. It’s impossible to write down everything that happened, but I’ve put up a few photos of some of our picnics and walks…we’d carry a couple watermelons or snacks, wander off onto the grassland, climb to the top of the hills, sit among the wildflowers, sing and dance, tell jokes…it was amazing.

Trip to Tso Ngonpo (Qinghai Lake)

Partway through the summer, Padma Reypa , Dhonden and I decided to go for a trip all the way around Tso Ngon Lake. I’d been wanting to do the trip for ages, so we organized a car and driver, and along with Dhonden’s mum, piled into the car in the wee hours one morning and set off for the trip. First stop was Chabcha (Gonghe in Chinese), where we took a break for breakfast, then carried on to Remola, the turnoff for the road to the lake, with its huge statue of Songtsen Gampo’s wife, the Chinese princess, who’d stopped here on her trip to Lhasa. Carried on past the town along roads through endless expanses of rolling green hills dotted with nomad tents and herds of sheep and yaks. Every so often there’d be a tea stop along the side of the road, with the traditional festive white tents and their colourful embroidered designs fluttering in the mountain breezes. We stopped once or twice, but for the most part motored on towards the lake. Topping the crest of a hill, the vast expanse of blue suddenly appeared, stretching off into the distance. The road took us right up along the southern shores of the lake, and we drove along, staring out the windows at the beautiful landscape of lakeshore, grassland and mountains. There were many small monasteries on the left side of the road, perched on the hills, with, I’m sure, incomparable views of the lake from the high windows. Chortens white against the rocky outcrops, and multi-coloured prayer flags flapping in the wind, I’d have loved to stop and take photos, but were on a schedule, and didn’t have much time to stop, unfortunately.

I’d like to come back another summer with my pack and tent, and go round the lake on foot. We drove on until we arrived at a small, extremely touristy village on the shore. We got out to have lunch, and stretch our legs, walking down to the shore to take some photos, avoiding all the touts who descended upon us on horseback or yak-back, trying to talk us into having our photos taken with the richly decorated animals. There were even people who had racks of traditional clothes that you could dress up in, to have your photo taken looking like “a native”! Mum and I had both worn our chubas anyway, so the disappointed vendors had to look for other victims. Tourist trade is extremely poor this year, because of the Olympics and the visa problems for foreigners, so we didn’t see any other Injees at all during our trip, despite the fact that Tso Ngon is usually a really popular spot to visit. Padma Reypa was bound and determined to take a boat trip out to some island, but our best efforts were in vain. The boat would only go out with a minimum of 70 people, or we’d have to pay the equivalent which worked out to some ridiculous price. Instead we took a small tourist boat, which just took us out onto the lake a ways to take photos, then came back. After that, we made a short detour to a tourist attraction, with a “typical Tibetan village” set up for people to wander round. It was all a bit of a laugh really, except that it was sad as well, considering the need for making a museum of a culture which should really be alive and working still. And it is in many areas of Qinghai, especially up in the nomad areas where the Chinese policies have made little impact, isolated as they are. Didn’t stay long there, but got back in the car to carry on our trip. Drove on as far as the Bird Island, famed for the flocks of cormorants which nest and hatch there eggs there each year. Had to get out of the car, get into a little trolley sort of bus, and then hike up a cliff to get to the viewpoint. Long before we arrived we could smell them, the rancid smell of rotten fish typical of seabirds. But it was very beautiful, and since it was getting on in the evening, we had the place to ourselves. Took the usual bunch of photos, while Mum had a rest, she was pretty tired from the long day, then headed back out to the nearby town to find a hotel to crash at for the night. The car and driver left that night; he had to get back for some reason or another, and after an early breakfast, we searched for a car to take us the rest of the way around the lake. After a fair bit of effort to get that sorted out, we drove off up and around the northern shores. The southern shore is much the prettier, but the northeast corner was also beautiful in its own way, with its huge drifting dunes of sand. I would have liked to stop off to see the big sand sculptures, but we were back on schedule, so no time for unplanned stops. Back to town, then on the bus back to Chabcha again for another night, and a quick trip out the following morning to see the chorten commemorating the Panchen Lama’s visit and teachings in Chabcha. Took a few photos, then were hustled back into the taxi to catch a bus back to Guinan

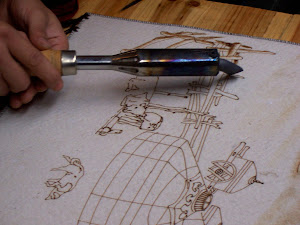

Thangka Painting

Just to fill in any spare hours that might possibly have dared to appear during my stay, I was asked to paint a thangka of the Tharshul monastery lama, Alak Yongzin, who had passed away just a few years before. I was quite pleased to do this, as I’d not done any painting while in Sichuan. It was fun to go out and try to figure out the equivalent to the materials I’d learn to use in India to stretch, prepare and then paint the cloth. As a result, several of the students decided they wanted to learn to draw as well, and we ended up with an art class of about 15, several of whom had quite a lot of talent. Aku Tashi, the abbot of Tharshul, is also very artistic himself, and has decided he’d like to learn western painting from me next time I come. He is the most unusual abbot I have met, very simple and kind, and very open minded, especially in education. He’s Sungrab’s older brother (another old friend from India), and he and I get along very well. He asked me to help make butter sculptures for display in the museum along with the mandala, but for various reasons which I will write about next, I didn’t end up having time to do them. He is saving that project for Losar. It took about a month and a half to finish the thangka, as I also had all my classes to prepare for an teach. The monks seemed to be happy with the result, and I’ve been asked to do another of Sambhota when I come back.

Rude awakening.

Because it was all so wonderful, one might have known it couldn’t last. I’d had some problems with the police during the summer. As I mentioned earlier, I very carefully did everything they had told me to when I was there at Losar, registered immediately when I arrived, gave them everything they wanted. Then they turned up one day, when Choezin and Aku Tashi and a few others were making the Kalachakra mandala in town, three of them, Tibetans, with a little booklet that listed the areas that foreigners are and aren’t allowed to stay in. Guinan was on the NOT list, along with most of the areas in Golok and a few other places. This meant I was only allowed to pass through, not stay, and they told me I’d have to leave before they got in trouble with their commander. I didn’t have much I could say, and told them they should talk to Choezin and Aku Tashi about it. But before they left, they also wrote down all the names of the students, since they were all not from Tharshul. I was less than impressed about this, getting into trouble myself was one thing, but I’d no wish for the monks to get in it as well. I was asked whether I was also teaching Tharshul monks, but denied this. At any rate, they left shortly after that, and I called Choezin telling him what had happened. He and Aku Tashi went to talk to the police, and it was eventually decided that I could stay, but was unable to leave the monastery, even to go to town to buy soap or toothpaste, because if the commander knew I was still there, they’d be in trouble. So I spent the summer in the monastery, basically under “house arrest” since, as usual, I’d ended up somewhere I wasn’t allowed to be. So what else is new. Just one thing that makes you realize how much we take our freedom for granted in the West. Earlier in the summer, just before the school holiday had begun, there was to be a big debate session, with scholars from all over Amdo invited. Many of them were monks, such as Jigme Gyaltsen from Rabgya school, as well as others equally famed for their knowledge, science and history teachers from various schools, and some of the top scholars from Tharshul monastery itself. They had been preparing for months,

Several of the chief guests had arrived, the tents were set up, and everything was ready, then late the night before it was to start, the police turned up, not only the local police, but also from the district headquarters in Chabcha. The whole thing was called off mere hours before it was to begin, the reason being that they hadn’t asked permission. All a bit ironic, because the police would have known ages ago, as there are moles in each monastery, letting the authorities know everything that happens, but nothing was done until the very last minute - a display of authority I suspect. Again, we just don’t realize how lucky we are in the West, what freedoms we have, until you have to try life without it, and find how incredibly frustrating it is. Control got tighter and tighter as the Olympics neared, and just a few days after school started back, all the students had travelled for days to return to school, it was announced that the school had to close. No reason was given. We found out later that several hundred Tibetan schools had been closed before the Olympics. We had had a picnic the day before, gone out to play games and sing. The other teachers knew already then that the school was to be closed, but hadn’t told us, as they wanted us to enjoy our picnic. Early the next morning, Shedup, Choezin and the other teachers came to my room to tell me. Aku Tashi came down, all the students were assembled, and they told us the authorities had announced the school was to be closed. The students had a week to go, and after that, the police would come and check to make sure the dorms and classrooms were empty. This news was greeted with silence, and then tears. For most of the monks, Tharshul is their only chance to study. The majority of them come from small monasteries, where there are so few monks that there is no debate or system of philosophy class. They spend all their time memorizing prayers, and little else. I felt so sorry for them, they are such an amazing, knowledge-thirsty group of young men, who’d travelled miles to this small school for the chance to learn, which they were now being denied. And for what reason? I know there is a lot of fear that there will be more uprisings during the Olympics, which will shame China internationally. But there have already been so many uprisings, the world knows all about it, and has still allowed them to host what used to be a symbol of international friendship and peace. What a joke. Anyway, excuse my digression…I’ve a lot to say about that which probably oughtn’t be said here. I also felt really bad for the teachers, all of whom had worked hard for their students, giving up a lot of their own time. All of them had come back from India, (which was probably part of the problem, since Tibetans, especially monks, who have returned from India are kept a close eye on.) and had put everything they had into the school. Aku Tashi too, had made the school his pet project, and paid close attention to the students and how they were doing. I was furious, as my western brain just couldn’t wrap itself round the fact that schools could be suddenly closed for no reason, on the whim of the authorities. We decided to hold a last party in defiance, so Aku Tashi planned a huge feast, and a day of games and songs as a farewell. It was a fun day, but one of definitely mixed feelings. Noone knew, or knows yet, whether the school will be permitted to reopen, so despite the fun and games, there was an undercurrent of sadness while everyone collected everyone else’s address and phone number, and made promises to keep in touch. For some, it was even more difficult, for example the monks from Sichuan, who couldn’t return home even if they had wanted to, as all the roads around the area they were from were blocked by the army, and monasteries have been closed down, thousands of monks sent away. In the end, there was a group of about 15 who decided to stay on as long as I stayed, to learn more English. Most of these were the original “Horrible Terribles”. So we set up a new schedule of classes, but it wasn’t with the same spirit of fun as the summer weeks had been. My time was ticking away as well, and there was always the fear that the police would find out a few of them had stayed, and force them to leave. Padma Reypa, Gedun Lekshey, Gyamtso and then Thupten Nyima left as well, for fear their staying would also create problems for the monastery.

Xining job hunt and visit to Parey

I left on the 30th of July, planning to go for a few days to Xining to check out the possibilities for work and extending my visa to stay in Qinghai rather than returning to Sichuan, but though I found loads of work, plenty of schools wanting an English teacher, especially one with experience who could speak Tibetan, I also found there was virtually no chance of getting a visa in Qinghai this year. All the foreigners teaching in Qinghai and Gansu are having to leave, their visas not being renewed in 2008. I spent one night in Xining, with Choezin, Aku Tashi, Padma Reypa and Gedun Lekshey. The next day, I visited a few schools with Phuntsok, then met up with Choephel in the afternoon, who demanded that Gedun Lekshey and I return with him to his home monastery in Parey, a stunningly beautiful area north of Xining on the Gansu border. We headed off with him, did a quick trip around the reserve with its beautiful scenery and waterfalls before returning to spend the night in his monastery, just a small place with 12 monks, but situated in a beautiful little valley, with fields and wooded hills behind, fields of wildflowers and a stream in front, and gardens full of hollyhocks, sunflowers and morning glory. The next day, Gedun Lekshey was itching to leave early for Repgong, as we planned to visit another school there, that might be able to make permits for teachers still, and then to visit his family in the hills. But nothing ever happens on time with Tibetans, so we set off late, drove off down to the town, and then had to sit in the car and wait while the driver, a friend of Choemphel’s, took care of some business. Choemphel finally got frustrated with waiting himself, so he hopped in the driver’s seat, much to our astonishment, and drove off jolting and lurching to another place he knew where we could take some more photos. Apparently he had learned how to drive a bit, and once we were actually moving, it wasn’t so bad, but every time he had to change gears, or start up from a stop, we were subjected to jolts and whiplash. To make matters worse, he chatted happily away, looking back at us over his shoulder to talk, paying no attention whatsoever to oncoming traffic or curves in the road. After nearly hitting a police car head on, we decided donning protective headgear might be a good idea, which did eventually convince Choemphel to keep at least one eye on the road. We finally arrived at the park, leapt out of the car to take photos of a high waterfall cascading down a cliff beside a huge rock painting of Buddha, and did a quick kora around the nearby chorten, (don’t know what they were praying, but I was begging for a safe return trip!) and then headed back to meet our driver. Got back without mishap, and carried on our way to town singing at the top of our lungs, stopping on the way to take some photos of the scenery eat some yogurt at a roadside stand take pictures of the famous white Parey yaks Gedun Lekshey and I were dropped off at the bus station, and we caught a bus back to Xining, promising to return to Parey with more time the next summer.

Repgong and scary motorbike trip up to Nomad-land

It was a hot 2 hour bus ride to Xining. One of the things I hate about bus travel in China is all the people who smoke. In Sichuan, at least there are signs forbidding it, to which you can point in disgust if someone lights up. Unfortunately, it’s often the driver. But in Qinghai all the men seem to smoke, not just one or two per ride, but one or two PACKS per ride. We arrived in Xining, hot and headachy, and decided to carry on to Repgong rather than spend the night in Xining. So we hopped on the next bus out for the 4 hour ride to Repgong. It’s a beautiful trip though. I’d done it in the winter last time, and it was stunning then too, through the Machu river gorge, past Jianza, and knowing one was nearing Repgong by the paintings on the cliff faces, announcing to all that Repgong is an area famed for it’s artists. I’ve long wanted to visit Repgong, home to Gedun Choemphel and many other famous artists, poets and scholars. The town didn’t disappoint, with paintings and poems everywhere on buildings and in the shops and restaurants. We booked into a tiny hotel in a back alley, or rather I did, while Gedun Lekshey went to stay with monk friends in Rong monastery in town. The next morning, we wandered around the monastery, where I could admire the painting to my heart’s delight, while he chatted with friends who came out with us. Several of my Tharshul students came from Repgong, and we met up with a few of them, even being invited to the home of one to meet his family. Had an amazing lunch with them, then walked over to ………monastery to visit one of the most famous thangka painters currently living in Repgong. He was very friendly, let me photograph his work, and brought us into a room full of his paintings, happy to bring out more. His chat quickly became very salesmanlike however, and we finally left, feeling we’d been invited in more as potential customers than to humour our interest. Ah well. His paintings were beautiful. Wandered around the monastery for a bit, but then had to leave to meet some of Gedun Lekshey’s family, who were going to take us to stay with his older brother and his family in the nomad summer camp up in the hills outside of Repgong. So off we went to the nearby village, where we were to meet his younger brother and nephew, who were helping build a house for some other relatives. Bit like the Amish system, everyone helps. They had about just finished stomping the clay for the roof into place when we arrived, so while we were waiting, we wandered off round the village for a bit, watching some villagers thresh canola seed, still using the traditional wooden rakes and throwing the seed up in the air with swift movements to separate the seed from the chaff. Finally made our way back, where I got on the back of the nephew’s bike (handsome young lad, about 18 years old, so shy he didn’t saya word the entire trip, bless him!) and Gedun Lekshey onto his brother’s bike. The “short” trip turned out to be about an hour, but again, I was so busy watching the landscape of mountains and cliffs carved into fantastic and surreal shapes by wind and snow over the centuries, a frothy river, rushing through dark rocky gorges, and rolling grassy hills, dotted with herds of sheep and yaks. After an hour, we pulled over at a “tea stand”, a couple traditional white Tibetan tents decorated with blue designs, which turned out to be another relative, the family of the nephew’s wife. (He scarcely seemed old enough to be riding a motorbike let alone have a wife, but apparently he’d eloped with her earlier in the year, and was now living happily with her and her family. Very romantic.) Were served dinner, momos of course, and the usual large greasy chunks of boiled meat followed by yogurt, while the men, the brother, and a bunch of friends who seemed to turn up out of nowhere began to drink. And drink. There were about 20 empty bottles scattered round by the time we decided to leave as it was beginning to get dark. Gedun Lekshey, the nephew and I had gone for a walk meanwhile, as GL doesn’t like watching people drink. I was loaded back onto the nephew’s bike, and given a jacket to wear, as it was starting to get really cold. The brother looked stable enough on his bike, as did his friend, and I figured they were probably used to drinking and then getting home via motorbike without killing themselves or anyone else. So we set off, but not on the road. Up a narrow, bumpy path directly up a hillside. The nephew had swapped bikes with the friend, so we were aboard a much more powerful model, which he was having difficulty controlling up the winding narrow path around the craters and hardened mud ridges left after the path dried in the rain. SO about halfway up, the friend was waiting for us, having watched out rather erratic progress, so we swapped back. Got a bend or two farther, then the engine sputtered out and died. No gas. The nephew was mortified, and told me to wait, that he’d be back soon with more petrol, so off he coasted downhill. Bemused, alone on a hillside in the middle of nowhere, I decided to keep walking along the path upwards, as it was too cold to just sit and wait. It was lovely walking along in the complete stillness, with just the sound of the wind rustling the grass and the occasional bird to break the silence. The perfume from some night-blooming flower filled the air, and I was quite happy to stroll along, until I heard the sound of a motorbike from above, and saw the brother coming back to see what had happened to us. Hopped on his bike and we roared off upwards to where Gedun Lekshey was waiting in the twilight with the friend on his bike. We swapped bikes yet again, and carried on, assuming the nephew would catch up eventually. It was getting darker and darker, and the path narrower and narrower, often on the very edge of the hillside. At least it was grassy as opposed to rocks, you would roll further but hit less if you fell off. But finally we crested the hill, and looked down into a wide valley with about 30 nomad tents scattered around, each one surrounded by herds of sheep and yaks, wisps of smoke rising into the night sky. I looked up, and saw millions of stars in the blackness, the milky way a smudge of grey. The only sounds were the lowing of the yaks, baaing of the sheep and the occasional bark of a dog.

Some of the tents were lit dimly within, and I found that the tent we were staying in had a single bulb powered by a small solar panel. We were served tea and yogurt, Gedun Lekshey’s sister in law looked after the fire and smiled shyly at us, his brother and older nephew sat chatting as more and more friends piled into the tent to see the strange foreigner who could speak Tibetan. While they were talking, I took the chance to look round the tent. It was different from the nomads’ tents in Mangra. There the stove was a long narrow platform, with room for cooking supplies, and the hearth and no more. Here, the hearth was wider, and connected to a large raised bed platform, with a sort of pipe shaped tunnel underneath where the smoke and heat from the fire kept the platform and sleepers warm. The tents in Mangra had come right down to the ground, with a strip of cloth tied round the bottom to keep out drafts, whereas here the actual tent was raised off the ground by a circular wall of smoothed clay, and outside, I saw the next morning, a narrow moat-like sort of ditch had been dug around the whole tent to control water runoff. In all, the tents here were a much more permanent sort of affair, whereas in Mangra, the nomads had to move more often, and could spend less time on the construction of their tents. After a couple hours of chatting and endless, bottomless cups of tea, I was struggling to keep my eyes open. The friends and neighbours started to file out, to return to their own tents, and no doubt to tell eagerly awaiting wives and daughters what the weird foreigner looked like. Gedun Lekshey was to sleep in the smaller tent nearby with his brother, the nephews had headed out into the darkness somewhere, and the wife told me she would sleep at a neighbour’s so I’d have the tent to myself. Would I be afraid? I thought not…by the time my head hit the pillow, I was already asleep. I was woken early in the morning by sounds of the sheep and yaks moving about, and the first rays of morning light through the tent walls. Shortly after that, the wife ( I never did find out her name) came in and started up the fire, then took her wooden bucket and hook out to do the milking, while the older nephew returned, gathered some bread and other food into an bag, and left to take the sheep up into the hills for the day. I crept out of the tent, shivering in the dawn air, as the full sunlight hadn’t yet penetrated the valley depths. I crouched to wash my face and brush my teeth, watching the women milking the yaks, some of whom were less than willing to be caught. The women do much more work than the men, all the cooking ad housework, all the milking, making butter, cheese and yogurt, walking down the valley to the river to wash clothes and fetch water in big plastic jerrycans which they strap to their backs and carry slowly back up the hill. After cooking and serving the meal, the women sit and wait until everyone has eaten before they wash the dishes and finally eat themselves. As they work, the men sit and smoke, chatting among themselves. I commented on this to Gedun Lekshey, and he agreed with me, saying he’d often spoken to his brother and nephews about it, but it’s difficult to change centuries of tradition, and the women themselves take it almost as an insult if you offer to help them. It was still cold in the valley by 7am, so we climbed higher on the hill, and watched the sun work its way into the depths of the valley, watching the camp bustling with energy, the sheep were already far up the hillsides with the shepherds, before the yaks were taken up after the milking was finished. One neighbour was loading here yaks with saddles and packs, taking them back to the village to pick up flour and other supplies. Children were shouting and playing, helping their mothers and aunts to place sheets on the hillsides, spreading chura (cheese curds) out to dry in the sun. After an hour, Gedun Lekshey’s sister in law shouted for us to come down for breakfast, tsampa and tea, and chunks of dry bread with butter. A few more neighbours came over to peer shyly in, and we sat outside to chat for a while and catch up on the news. Gedun Lekshey had been away all summer at Tharshul, so everyone had lots of questions for him. But not long afterwards, we set off to visit his mother and other family in their village.

Trek to the family village, then more trekking to the monastery

There was no road to this village, just a 3 hour walk along narrow paths up the hill. So off we went, trailed by several old people and many kids, who kept us company until we reached the top of the hill, then set off back, shouting and singing while we carried on down the other side. It was beautiful, no cars or motorbikes, no people apart from us, just the wide expanse of valley with hills sloping up either side, covered in flowers, birds soaring in the wind currents, and the occasional wild pheasant rustling in the long grass. It was hard to walk and pay attention to the ruts in the path when I wanted to be looking around. Gedun Lekshey strode ahead, reciting his daily prayers so that he’d have time later to talk with his family, so I followed happily, gazing round until I tripped over a stone, then watching the path until my attention was distracted by the view. Every once in a while, I picked a wildflower along the path to press, thinking I could send them back for Mom to see, and show my old friends at Sharples. We stopped once for a bit of a rest, but I wasn’t tired at all, having adapted to the high altitude at Tharshul, I found I had no problems scrambling up the hillsides here.

After a couple hours, Gedun Lekshey pointed to the opposite hilltop, and pointed out his village. It was just an hour from there, down into another valley, with fields carpeted in forget-me-nots so blue the entire field looked blue from above. We forded a stream, pausing to wash our dusty feet, then started up the hill to where we could see his mother and aunt watching us approach. They had been watching us for hours, seeing us as a speck of white and red far away on the hills. We were led indoors with excitement, where we were fed yet again with cups of steaming tea, yogurt, meat and bread. Gedun Lekshey’s younger brother and his wife were both there. The wife is from Shigatse, near Lhasa, and spoke very little Amdo dialect, so it must have been hard and lonely for her, but she didn’t seem to let it get to her, and was cheerful and helpful. She came from a farming family, and had worked in shops and restaurants, so had no idea how to do the nomad work. As a result, she was living in the village with the old people, as all the others had gone off to the summer nomad camp with the sheep and yaks. We chatted for a bit, and I brought out my family pictures, which are getting very dog-eared and battered after a summer of being shown round everywhere I go. These elicited the usual exclamations of delight, and the usual comments on how big kids aged 2 or 3 are compared to kids of the same age here. We sat for a bit, then went out to climb a hill, where Gedun Lekhey showed me all the places he used to play as a child, and tell me stories about when he was growing up. For dinner, the old uncle was hard at work to make sausages made the Amdo way, mincing piles of meat and liver, mixing them in a large pile with handfuls of flour and chopped green onions. This was then stuffed into long loops of freshly washed intestine. The whole process looked quite gruesome, especially when you’ve been vegetarian for so many years. This was then chopped into manageable lengths, and stuffed into a big pot, where it was steamed for several hours on the clay stove. As it got dark, everyone gathered in the room, sitting round the fire with bowls of sausage and chilli sauce to dip it in, cups of tea and chunks of bread. Most of the houses I’ve been in are fairly similar, smoothed clay walls and floor, the walls often with garishly coloured posters of fruit or waterfalls to liven them up, the family altar in one corner, with photos of various lamas or deities, butter lamps and incense lit beneath, and the usual row of little bowls of water, carefully cleaned and refilled each morning. Some part of the room is always taken up by the bed platform, on which several or many members of the family will sleep. In the morning, the blankets and rugs are all folded tidily up against the wall, to be taken out at night, thus allowing the bed to act as a seating place during the day. This platform is usually connected by pipe-like tunnels beneath, a very efficient heating system, excellent during the long cold winter months.

The next morning, early after breakfast, we left on foot again, to walk for several hours again to visit Gedun Lekshey’s monastery. There was no road there, so it was to be another hike, this time down the riverbed, then up another couple hills. Getting there is half the fun is certainly true for this part of the world. Like yesterday, while GL did his prayers, I entertained myself with looking around, gathering more flowers, and singing to myself. The monks had been calling frequently the past few days. “So when are you coming?” “Are you coming yet” “Where are you now?” “Are you bringing the teacher?”

When we got close, we could see them running out to meet us. It still being Yarney, I wasn’t allowed in the actual monastery compound, but the monks had set up a tent for me on the hilltop facing the monastery, on the edge of the woods, with a beautiful view of the surrounding mountains and forests. We dropped our stuff inside, just as a group of monks turned up, lugging small tables, and boxes of fruit, drinks, sweets and bread. Soon there was about 15 of us, sitting round on carpets, talking and laughing. Jigme Oser is from this monastery as well, and I’d not seen him since India either, so it was good to catch up on news and show and see photos. There was a grand feast that night as well, of course, platefuls of meat and vegetables, bread and of course yogurt. We sat up talking until late, then they all headed back to the monastery, and I was left to curl up in the mountainous pile of blankets they had brought for me. Got up early the next morning to wander around my hilltop and take some photos, before breakfast was carried up to me. The whole lot turned up again, and we had a photo taking session for about an hour before it was time to go again, on motorbikes again this time, on a road of sorts, as opposed to walking.

Wendu monastery, sacred pillars and back to Repgong

Two monks took Gedun Lekshey and I off down the road towards Repgong, but we stopped forst to visit Wendu Monastery. This big beautiful monastery was the monastery of the Panchen Lama, and was about a 2 hour ride up and down dusty roads through yet more stunningly beautiful scenery, past loads of little monasteries perched precariously on hilltops, and villages nestled in valley bottoms, alongside rushing rivers, most with one or more startlingly white chortens set among the houses. This whole region is famous for having produced many famous lamas and scholars, the most famous of whom was the 10th Panchen Lama. We went into the monastery, where Gedun Lekshey had yet more relatives, and the monks and I went off for a tour of the monastery and its precious chorten while GL chatted with another nephew. Wendu is quite large still, with about 300 monks, and has a working education system and debate, though not to the extent of the monasteries in India. After an hour or so of looking round the main prayer halls and taking yet more photos, we returned to the nephew’s rooms, had a quick cup of tea, and climbed back on the bikes for another detour, this time to visit the Panchen Lama’s birthplace, his family’s home, which is now a small museum of sorts, a pilgrimage spot, where you can see the pillar against which his mother leaned to give birth to him. The caretaker there was a rather grumpy monk, who was less than helpful and said we could only visit downstairs, as the upstairs was off-limits to forigners.

My monks were quite annoyed at his behaviour, so we didn’t stay long, and got back on the bikes to return to the cutoff for Repgong, to catch the bus to town. We were covered in dust at this point, my black pants were grey, and my hair was chunks rather than strands, so I was looking forward to a shower to get rid of several kilos of grime. The bus that was supposed to come at 3pm finally turned up at around 5, and we clambered aboard grateful to be moving again at last, while Thamkey and Tenzin (the monk friends) started back up the hill to go back to the monastery before dark.

Arrived in Repgong late that night, but a shower took precedence over sleep. Next day GL and I started the process of meeting the people in charge of getting the visas for foreign teachers at the school. Went first to meet the previous headmaster, who turned out to be an old friend of Gedun Lekshey’s family. Chatted with him and his wife for a while, then he called his daughter, a science teacher in the school who was also the link between the school and the foreign teachers. She was away, but promised to come back the next day to meet and talk with us. Also, the current teacher, Charlotte from South Africa, was due back the next day, so we arranged to get together and discuss the whole visa issue. Spent the rest of the afternoon wandering around town, less fun in some ways than the previous time, since it was the 8th of August, the first day of the Olympics, and there were military vehicles everywhere, and groups (platoons? squadrons? I’m afraid my military terminology isn’t up to par, sorry) of armed soldiers marching up and down the streets, to show their presence, and keep the population submissive. Repgong is an area primarily Tibetan, in contrast to places like Xining, where there is a great umber of Chinese. I liked Repgong much better, particularly as you can get around the town speaking just Tibetan. My Chinese is still pretty much non-existent. I don’t seem to have picked up much at all. My own fault I suspect. I don’t find it an attractive sounding language, and my lack of interest and probably bias against it has stopped me from learning much. Ought to get over that really, as you really do need to speak a little at least to get around. China’s not like many other countries, where there’s always someone in the train station or post office who speaks at least a few words of English. But in Repgong, most of the taxi drivers and shopkeepers speak Tibetan, which made it much easier to get around. The next day, we had the meeting with Lhamo-kyen (the daughter) and Charlotte. We then went to meet the current headmaster. It turned out that the school itself had just had its permit for having foreign teachers withdrawn for 2008, as had most of the other schools in the area. This particular school had had 3 teachers the past year, two of whom had left when their visas weren’t renewed, and Charlotte was only still there, it turned out, because she’d been on holiday in Golok when the police came to revoke the permit, and they’d been told she was gone. Her visa is due up in November, and she’s not sure either whether she’ll be able to stay. That’s the problem working here. You never know if the work you’re doing or the projects you start will actually be able to continue. Frustrating it is. They were keen to have me return in 2009. No shortage of teaching jobs, just the wretched paperwork for the visas. They don’t make it at all easy for foreigners to teach in the Tibetan areas, whereas in Sichuan they are desperate for teachers since most people left after the earthquake, and there are not exactly queues of people waiting to come in their place. Most of my foreign friends in Chengdu have left. But for all intents and purposes, there’s no chance for a visa in Qinghai this year. Will have to wait until the dust settles from the Olympics, and see what the situation is like next year. Spent a quiet afternoon with Gedun Lekshey and friends at the monastery, had a final dinner with Jinpa and Dargye (students from Tharshul) then got on a bus early the next morning to return to Xining, while he returned to his monastery.

Xining-Chabcha-and the final days at Tharshul

Uneventful trip back to Xining. I was returning with very mixed feelings, realizing that I’d have to return to Sichuan again for another year, and trying to think of other options.

As always though, with bus travel here, despite the clouds of cigarette smoke, the scenery takes one’s mind of things. I always wish I could stop the bus, leap off and take photos of the soaring mountains wrinkled with crevasses, a study in chiaroscuro, especially in the late afternoon, when the light turns golden, and the sky deepens to an unbelievable blue. The landscape here is ruggedly beautiful, and you can understand how the Tibetans have become the people they are living here. Although China encourages Chinese settlers to move here, and allows two children per family rather than the usual one, for the most part, the Chinese live in the cities or the places where farming is a viable way of life, while the Tibetans keep to the hills. Repgong is perhaps one of the few exceptions, but then it has traditionally been a stronghold of Tibetan culture and arts. Back to Xining, spent just an hour or two there before my next bus was to leave for Chabcha. (Gonghe in Chinese). I had decided to give the Xining-Thrika bus a miss this time round, and take the longer but faster and more comfortable journey to Mangra via Chabcha. Besides, I had quite liked the town during the brief stopover we’d made en route to Tso Ngonpo, and wanted to explore a bit on my own. Arrived late-ish in the evening, around 6pm, and looked for a Tibetan hotel to stay in. Found one right in the middle of the market area, dropped off my stuff and set off to wander round the market. There are a large number of Chinese in town as well, but the market area is primarily Tibetan, so I meandered my way through stalls selling prayer flags and rosaries, loads of tailor shops making and selling Tibetan clothes, more shops selling brick tea and huge chunks of butter – shops that probably haven’t changed much since the days when the Silk Road caravans travelled across Asia. Sat and chatted with a few of the shopkeepers, being offered yet more cups of thick milky tea and showing yet again the photos from home. Around 8pm, found a restaurant and sat down to a dinner of momos and tea, watching the Chinese win yet more golds in weightlifting. How many weightlifting events were there this year anyway? Not that it’s ever been the most enthralling sport to watch, but there seemed endless categories of weightlifters this year. Decided chatting with the other customers was more fun, they had stared at me in amazement since I ordered my meal in Tibetan, so I was invited over to join their table, and we talked for an hour or so. The next morning, I wandered round a bit more, before catching a bus out to Guinan at noon. Had met Choezin, who was in town with several other monks doing shabden, and he’d called Aku Tashi to arrange for a car to meet me at the turnoff to Tharshul on the way back, so I’d not have to go into town and possibly be seen by the police. The bus was crowded with Tibetans and Muslim Chinese, but I sat quietly near the front, until a few Tibetans got on at Tharshul town. One of the guys who got on sat behind me, and a few minutes later handed me his cell phone. I had no idea what he was doing, since I’d never seen him before, but he had called a friend, telling him there was a foreigner on the bus, and to talk to me.(I’m the first foreigner many of the locals had ever seen. This isn’t exactly an area that tourists visit.) In astonishment, I took the phone from him, and it turned out to be Sungrab! He was as surprised as I was, and we chatted for a while. He was waiting with his truck at the Tharshul road waiting for me, Aku Tashi having called him an hour or so before, telling him I was coming. Small world. After that conversation, all the Tibetans on the bus started talking with me, and I’ve enough invitations now for dinner or visits to homes to keep me going for a good month when I return. About 20 minutes later, we arrived at the turnoff, and I was handed down to Sungrab. It was lovely to be bouncing along the pitted track “home” to Tharshul.

It was already the 10th of August however, and I’d only a few days to spend at the monastery, since I was technically supposed to be back in Chengdu on the 15th. I’d decided a day or two wouldn’t matter in the scheme of things. They need teachers so badly, that I knew visas would be sped up just to get people to stay, and I was in no rush at all to return. So I planned to leave Tharshul on the 14th for Xining, spend a couple days there, and get back to Chengdu on the 17th or 18th. The students were all waiting for me, bless them, but they had to go off to do a day of prayers for Rapsel’s family. As this is their sole way to get any money, it wasn’t fair to cancel that plan, so while they went off to do the prayers, I had a day hanging out with Khenrab and climbing the hills around the monastery on my own, enjoying my last days of space solitude and clean air. That day, Konchok called to tell me to make sure I was around to see the huge appliqué thangka being unrolled on the hillside for cleaning. It is unveiled once a year during Monlam, which I had missed, having had to leave early to visit Jianza and Labrang after Losar. But it’s also taken out once during the summer, to check for mildew and moths, and to shake out any dust. It was quite the occasion, with most of the monks present. The had carried it up the hill and unrolled it, pulling up the yellow silk protective cover, and were trying to shake off as much dust as they could. It was so huge however, that just shaking it wasn’t proving terribly effectual, so the young novice monks were told to run uphill beneath it, waving their arms to shake the cloth. This of course turned into a vastly entertaining sport, with the young monks trying to race each other uphill, sliding on the slippery grass. It seemed more of a game than an actual effort to clean anything, and the older monks just laughed in sympathy with the kids’ high spirits. Finally, it was declared clean for the year, and the rerolling process began. Meanwhile, I was taking pictures of the whole event, and monks whom I’d not met, but obviously knew who and what I was came over to chat and have their photos taken. Once rolled up, the thangka was whisked away down the hill, back into storage until Monlam.

The students were back that evening, and we spent most of my remaining time in the monastery together, cooking and eating meals together, and looking back through the photos from the summer, laughing, reminiscing and planning our next meeting at Losar.

I knew I was really going to miss them, we’d got to be very close over the summer with its joys and hardships.

Xining again, then back south to Chengdu

Finally the morning of the 14th arrived, no matter how much I’d hoped it wouldn’t come.

All my friends gathered to see me off, and back I went to Xining, to spend a couple days with Phuntsok and Paljor before returning south. Phuntsok is one of my oldest friends here. He had been one of my first students when I arrived in India and was teaching at Dharamsala for a year in Yong Ling school before going to teach in Mundgod. I had met him in Chengdu earlier, and then at Losar, but now he’d moved into his new place, and it was lovely to spend some time with him, drinking coffee (REAL coffee, yay!) and talking English. His English is very good now, as he spent several years studying in Dharamsala after I left for the south, and then came back here to start his own travel /tour agency. Met up with Paljor and a few other friends, met a couple American girls, Alyson and Stacy. Alyson is planning to come down to Chengdu later in the year, and will probably come stay with me for a bit. Not much else of excitement to report from Xining,

Got on the train to come back south. Unfortunately, no sleeper berths available, so it was a loooong 30 hour trip back on a hard crowded seat. Very quiet too, as all the other passengers were Chinese, so I could sit and muse to my heart’s content. The closer we got to Sichuan, the hotter it became. The landscape outside more developed and inhabited, Fields of rice and vegetables lush in the bright sunlight. Then as we neared Chengdu, the sky became greyer and smoggier. I already miss the clear blue of Qinghai’s mountain skies. Finally pulled into Chengdu station, and I hauled myself off the train and through the milling throngs of humanity to the taxi stand. Arrived back at Wuhou ci, and booked myself in at Holly’s, feeling as though I’d never been away. Decided to spend a couple days in Chengdu before heading back to school, treating myself to a few days of nothingness, and to coffee and truffle cake at Starbuck’s. I’d started thinking of running off to Thailand for a couple months, then trying to get a visa to teach up in Repgong in December or January rather than returning to Santai. Have been considering it very seriously in fact. I’ve good friends there, who have been inviting me to stay for years, so I’d have little expenditure beyond whatever tourism I decided to do. Flights from Kunming are cheap, I discovered….the only thing stopping me is that I want to go back to Qinghai for Losar, and the visa situation here is so unstable right now, that there is no guarantee I’ll be able to get the visa to return. So things are still in limbo. At this point, I’ll probably end up staying here. Not so bad really. I kno once I start teaching again I’ll be fine, it’s just a matter of getting my head round being back here again, and getting over missing my friends and students up north. But after all, it’s only for a month to begin with, as the first week of October is a holiday apparently, and I’m taking a couple weeks off later that month to meet more friends. Then just November and December, as the Chinese lunar New Year falls on January 25 this year, and I’ll have the couple weeks off before that, as the kids have exam prep and then exams. Then back to Tharshul for Losar…The practical, logical bit of me says “stay, save up some money, and work out how to move north next year.” The less practical part of me (the bigger part!) says “what are you thinking? Bugger off to Thailand – the beaches, the food…I’ve wanted to go to Thailand for ages…” So this is my quandary, which is as of yet unresolved…haven’t signed any contracts yet…Am going into Chengdu tomorrow, so will have to make my decision then, I expect. So I end this epistle on that note…you’ll all know soon anyway depending on where my next emails are from. At the moment, I’m back in my flat, catching up on my emails and correspondence, preparing for classes in the event that I do stay, and hiding from the general public drinking coffee and watching pirated movies

I ought to have learned my lesson after the last trip to keep a proper journal while away, but sense and logic have never been among my better qualities, as all of you who know me well can confirm. So here I sit yet again, trying to write an entire summer’s worth of stories into a few paragraphs that won’t take absolute days for you all to read.

The last day of my contract was May 30. I had classes in the morning, and had packed all my stuff ready to go, so that I came back to my flat, dumped my books, picked up my pack and was off. The other teachers and students, bless ‘em, still had a good month or so to go and all the exams to take. I was more than happy to leave for various reasons, one of the main ones being to head for the hills and ground that didn’t shake! Spent just a night in Chengdu, and was on the train the next day for Xining. Fairly unexciting train ride, I slept most of the way. It was several hours longer than last time, as we had to detour around the earthquake damage at Mianyang, but finally arrived around mid afternoon, and I got a taxi over to Phuntsok’s. Spent just a night there as well, as I wanted to catch the first bus I could back to Tharshul. A much warmer ride than the one I made at Losar, where my feet had frozen in solid bricks hours before I arrived. It was nice to sit and enjoy the scenery without having to stomp my feet in order to prevent getting frostbite.( This does tend to distract just a wee bit from one’s overall enjoyment of the landscape, I find.) Took the bus via Thrika (Guide) again, though should have asked whether the construction begun last year had been completed. I was in the very last row of seats, and after leaving the highway to Thrika, we drove for about 6 hours on a “road” that seemed to largely consist of potholes and large rocks, which I suppose at some point will be used to make the road smooth, but at that point seemed to serve the sole purpose of bouncing all the passengers in the back half of the bus off the roof. I vowed an hour into the drive never to take that route again without a crash helmet. And the rocks and potholes were the least of our worries a few hours later. The road had been literally washed down the side of the mountain by heavy spring rains, and a temporary track of sorts had been scraped into the side of the cliff, often at a 45 degree angle, so that those of us on the right side of the bus found ourselves staring straight down the cliffside into a valley full of huge boulders and other debris obviously the result of fairly recent landslides. Those on the left side had an only slightly more reassuring view of the scree covered cliff rising high above, dotted with signs warning of avalanche. After a few hours of rattling along uneven roads on the mountainside, inching our way on temporary tracks around bridges that had collapsed and carefully not looking down at rusted wrecks of vehicles at the bottom of valleys, one does seem to become somewhat immune to the terror or imminent death, and the discomfort of being banged and bounced around becomes the more overriding concern. At any rate, we did eventually arrive in one piece, (a slightly bedraggled, shaky piece, but one piece for all that) and the landscape between bounces was stunning. Got into Mangra (Guinan) several hours late, to find all the guys waiting for me. Just like coming home, it was lovely to be taken straight to a restaurant for lunch and a quick wash. Then off to the police station to register my arrival – a lesson learned the hard way from my Losar trip – and everything seemed fine, filled out the usual form, handed over a Xerox of my passport and a photo, then we all piled into a car and headed for the monastery. How green everything was, the fields full of wildflowers, and the nomads’ tents and yaks dotting the hillsides. No smoke or smog, and miles and miles of blue sky, hills and hardly a human in sight.

Pulled up to the monastery school, which had been closed for the holidays during my winter visit, and was shown into the room which had been prepared for my arrival. Nice to have my own space, complete with a bathroom and HOT WATER! That had been the only real drawback last trip, not being able to shower at all apart from 2 or 3 trips to town and the Muslim bathhouse. The students were in class, 60 monks ranging in age from 15 to 30 from all over Amdo (Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan). They were as curious about me as I was to meet them, but there was no time the first day, as I was hurried off for dinner, and spent most of the first evening catching up on the latest news with my friends.

The next day was to be my first day of classes (no rest for the wicked…!). Choezin did sit in on the first day’s classes, to make sure the students could all understand my hybridized version of Amdo dialect. The first class is always hard, especially mid term when you don’t know what they have already learned, or what level they are at. They were all really shy, but that soon wore off after the next few days. I had however, arrived just shortly before the midterm exams, and the students were to have a 20 day summer holiday. Up here, the summer holiday is short, and the winter holiday longer, because of how cold it is in dorms and classrooms that are unheated. So I helped with the exams, then found out that 14 of the students had decided not to go home for the holidays, but to stay and learn English. So we set up a schedule that ended up with them having 4 classes a day, 2 of which were open to other monks from the monastery as well, Rapten, Namgyal and a few others who had studied with me during the Losar holiday. I also had 2 classes a day for Choezin, Shedup, Ngawang, Khenrab and also Padma Reypa (an old, old friend from Gomang, now the abbot of a big Nyingma monastery in Golok) Gedun Lekshey (another old friend from Gomang, from near Repgong), Gyamtso and Thupten Nyima (also Gomang monks, from Thrika). This group are all friends from India, and several of them had travelled up to stay at Tharshul for the summer to study English again. So in total, I ended up teaching 6 classes a day, 2 in the morning, 4 at night, and drawing class all afternoon.

Horrible, Terrible crazy students…..!

The group that stayed for the holidays became really close friends. We cooked together, ate together, went for walks and had picnics, and spent hours laughing together. We all ended up with various nicknames, many with long stories behind them, which are probably only funny if you were there, so I’ll spare you the details on that! We called ourselves the Horrible Terrible crazies…and our group included: Jinpa, from an area near inner Mongolia, Choegyam, Shedup and Konchok from Tseko, Black Konchok, Dorje and Gyamtso from north Sichuan, Longtok, Chedak and Tashi Nyima from Tso Ngonpo (Qinghai Lake), Damchoe from near Labrang, Jinpa from Jianza, Paljor. And Choezin’s nephew Tsegya, who’d studied with me at Losar as well during his school holidays.

We became close friends, aided by the fact that it was Yarney (the monastic season where the monks aren’t permitted to leave the monastery, and no women are allowed in, not even the monks’ mothers. There are various other rules, such as no cutting grass, or walking on grass if it can be avoided. This is to make the monks remember all the lives of bugs and small creatures that are taken by people blindly tramping on the grassland) So although I’d been told I was an exception to the rule, and was allowed in the monastery grounds, I was careful not to abuse the privilege and offend the senior monks, so I stayed in the school compound beside the monastery, and friends came over to see me. That meant I spent all my time with the students in the school, and we worked hard at lessons.

That group worked really hard at their English during those 20 days, and improved more than I’ve ever seen any group of students do in such a short time. They attended 4 classes a day, chatted and joked with me during mealtimes, and when assigned 10 sentences for homework, did 50. I gave them 2 “exams” to judge their progress, and was incredulous at how well they did. We decided to hold an exhibition type competition for the first day of regular classes when all the students returned, and we practiced hard for a week beforehand, inviting Choezin and the other teachers to watch our progress. On the day of the actual competiton, we invited all the teachers, Aku Tashi, the Gomang monks, and anyone else who cared to watch to come and see. I was really proud of them, and they were proud of themselves, almost in awe at how much they’d learned in such a short time. Sungrab turned up, and was really impressed with how much they could understand and talk. The way I set up the competition was to divide them into two teams, fairly well balanced in ability levels, and made a large dice out of cardboard. If they rolled a 1 or 2, they had to define and spell a vocabulary word (they’d memorized 50). If they got a 3 or 4, they had to translate my Tibetan sentence to English, and a 5 or 6 meant they had to translate my English sentence to Tibetan. It was a lot of fun, and we spent as much time laughing as learning during our 20 day “summer school”. I have never had such a good group of students, one that worked so well together and had such a bond of camaraderie.

Even the students returning commented on how they wished they’d not gone home, since they had really missed out on a great summer. It’s impossible to write down everything that happened, but I’ve put up a few photos of some of our picnics and walks…we’d carry a couple watermelons or snacks, wander off onto the grassland, climb to the top of the hills, sit among the wildflowers, sing and dance, tell jokes…it was amazing.

Trip to Tso Ngonpo (Qinghai Lake)

Partway through the summer, Padma Reypa , Dhonden and I decided to go for a trip all the way around Tso Ngon Lake. I’d been wanting to do the trip for ages, so we organized a car and driver, and along with Dhonden’s mum, piled into the car in the wee hours one morning and set off for the trip. First stop was Chabcha (Gonghe in Chinese), where we took a break for breakfast, then carried on to Remola, the turnoff for the road to the lake, with its huge statue of Songtsen Gampo’s wife, the Chinese princess, who’d stopped here on her trip to Lhasa. Carried on past the town along roads through endless expanses of rolling green hills dotted with nomad tents and herds of sheep and yaks. Every so often there’d be a tea stop along the side of the road, with the traditional festive white tents and their colourful embroidered designs fluttering in the mountain breezes. We stopped once or twice, but for the most part motored on towards the lake. Topping the crest of a hill, the vast expanse of blue suddenly appeared, stretching off into the distance. The road took us right up along the southern shores of the lake, and we drove along, staring out the windows at the beautiful landscape of lakeshore, grassland and mountains. There were many small monasteries on the left side of the road, perched on the hills, with, I’m sure, incomparable views of the lake from the high windows. Chortens white against the rocky outcrops, and multi-coloured prayer flags flapping in the wind, I’d have loved to stop and take photos, but were on a schedule, and didn’t have much time to stop, unfortunately.

I’d like to come back another summer with my pack and tent, and go round the lake on foot. We drove on until we arrived at a small, extremely touristy village on the shore. We got out to have lunch, and stretch our legs, walking down to the shore to take some photos, avoiding all the touts who descended upon us on horseback or yak-back, trying to talk us into having our photos taken with the richly decorated animals. There were even people who had racks of traditional clothes that you could dress up in, to have your photo taken looking like “a native”! Mum and I had both worn our chubas anyway, so the disappointed vendors had to look for other victims. Tourist trade is extremely poor this year, because of the Olympics and the visa problems for foreigners, so we didn’t see any other Injees at all during our trip, despite the fact that Tso Ngon is usually a really popular spot to visit. Padma Reypa was bound and determined to take a boat trip out to some island, but our best efforts were in vain. The boat would only go out with a minimum of 70 people, or we’d have to pay the equivalent which worked out to some ridiculous price. Instead we took a small tourist boat, which just took us out onto the lake a ways to take photos, then came back. After that, we made a short detour to a tourist attraction, with a “typical Tibetan village” set up for people to wander round. It was all a bit of a laugh really, except that it was sad as well, considering the need for making a museum of a culture which should really be alive and working still. And it is in many areas of Qinghai, especially up in the nomad areas where the Chinese policies have made little impact, isolated as they are. Didn’t stay long there, but got back in the car to carry on our trip. Drove on as far as the Bird Island, famed for the flocks of cormorants which nest and hatch there eggs there each year. Had to get out of the car, get into a little trolley sort of bus, and then hike up a cliff to get to the viewpoint. Long before we arrived we could smell them, the rancid smell of rotten fish typical of seabirds. But it was very beautiful, and since it was getting on in the evening, we had the place to ourselves. Took the usual bunch of photos, while Mum had a rest, she was pretty tired from the long day, then headed back out to the nearby town to find a hotel to crash at for the night. The car and driver left that night; he had to get back for some reason or another, and after an early breakfast, we searched for a car to take us the rest of the way around the lake. After a fair bit of effort to get that sorted out, we drove off up and around the northern shores. The southern shore is much the prettier, but the northeast corner was also beautiful in its own way, with its huge drifting dunes of sand. I would have liked to stop off to see the big sand sculptures, but we were back on schedule, so no time for unplanned stops. Back to town, then on the bus back to Chabcha again for another night, and a quick trip out the following morning to see the chorten commemorating the Panchen Lama’s visit and teachings in Chabcha. Took a few photos, then were hustled back into the taxi to catch a bus back to Guinan

Thangka Painting

Just to fill in any spare hours that might possibly have dared to appear during my stay, I was asked to paint a thangka of the Tharshul monastery lama, Alak Yongzin, who had passed away just a few years before. I was quite pleased to do this, as I’d not done any painting while in Sichuan. It was fun to go out and try to figure out the equivalent to the materials I’d learn to use in India to stretch, prepare and then paint the cloth. As a result, several of the students decided they wanted to learn to draw as well, and we ended up with an art class of about 15, several of whom had quite a lot of talent. Aku Tashi, the abbot of Tharshul, is also very artistic himself, and has decided he’d like to learn western painting from me next time I come. He is the most unusual abbot I have met, very simple and kind, and very open minded, especially in education. He’s Sungrab’s older brother (another old friend from India), and he and I get along very well. He asked me to help make butter sculptures for display in the museum along with the mandala, but for various reasons which I will write about next, I didn’t end up having time to do them. He is saving that project for Losar. It took about a month and a half to finish the thangka, as I also had all my classes to prepare for an teach. The monks seemed to be happy with the result, and I’ve been asked to do another of Sambhota when I come back.

Rude awakening.

Because it was all so wonderful, one might have known it couldn’t last. I’d had some problems with the police during the summer. As I mentioned earlier, I very carefully did everything they had told me to when I was there at Losar, registered immediately when I arrived, gave them everything they wanted. Then they turned up one day, when Choezin and Aku Tashi and a few others were making the Kalachakra mandala in town, three of them, Tibetans, with a little booklet that listed the areas that foreigners are and aren’t allowed to stay in. Guinan was on the NOT list, along with most of the areas in Golok and a few other places. This meant I was only allowed to pass through, not stay, and they told me I’d have to leave before they got in trouble with their commander. I didn’t have much I could say, and told them they should talk to Choezin and Aku Tashi about it. But before they left, they also wrote down all the names of the students, since they were all not from Tharshul. I was less than impressed about this, getting into trouble myself was one thing, but I’d no wish for the monks to get in it as well. I was asked whether I was also teaching Tharshul monks, but denied this. At any rate, they left shortly after that, and I called Choezin telling him what had happened. He and Aku Tashi went to talk to the police, and it was eventually decided that I could stay, but was unable to leave the monastery, even to go to town to buy soap or toothpaste, because if the commander knew I was still there, they’d be in trouble. So I spent the summer in the monastery, basically under “house arrest” since, as usual, I’d ended up somewhere I wasn’t allowed to be. So what else is new. Just one thing that makes you realize how much we take our freedom for granted in the West. Earlier in the summer, just before the school holiday had begun, there was to be a big debate session, with scholars from all over Amdo invited. Many of them were monks, such as Jigme Gyaltsen from Rabgya school, as well as others equally famed for their knowledge, science and history teachers from various schools, and some of the top scholars from Tharshul monastery itself. They had been preparing for months,